PART FIVE

4.4 From Near Completion to Public Auction, 1885-1899

With work now stopped, Wilson stressed to NHC that the need to continue was critical to avoid serious delays as the work was being done tidal. While awaiting a restart, an agreement was reached with Daniel for £5,500 (*£723,000) as payment for the recently arbitrated claim. However, NHC now sought to terminate Daniel’s contract. On the 18th August, it was mutually agreed to fully discharge Daniel from his contract at a cost to NHC of £10,500 (*£1,380,000), including the £5,500 arbitrated claim. Payment was to be £2,000 (*£263,000) immediately, £2,000 in September, £2,000 before 18th October, the balance of £4,500 (*£591,000) within a year. As a consequence of ending this contract, NHC now had to deal directly with suppliers, paying Armstrong for the hydraulics, Vernon & Ewens, Cheltenham for the lock gate works, and The Phoenix Foundry Co., Derby for the draw-bridge and associated opening machinery. All would be paid for work-to-date and all were to continue with planned work.

At the earlier meeting on 7th July, the cheque due payable to Wilson for his professional services was deferred with no reason being given. In what was to be the final report by Wilson on 3rd August, he urged for the maintenance of slopes and slagging of banks, or they would be washed-away, and due to the extent of excavations in the basin, the walls needed to be secured. An NHC meeting, on 28th August, documented that they had in fact earlier dispensed with the services of Wilson as of 7th August and had proposed to him that he either resign or they would terminate his contract. However, he would only retire under certain, quite onerous, at least to NHC, terms. This remained unresolved and was placed in the hands of their respective solicitors. In October, there was at least resolution of this matter, with Wilson, who had initially refused to hand-over all plans etc. to Brereton, proposing that full payment up to July, 1885 would suffice as long as he was fully discharged from the contract. NHC agreed.

The relatively harsh treatment of both Daniel and Wilson by NHC over the latter stages of their employment may have had a number of causes. Possibly, NHC remained disgruntled over their lack of communication regarding the nature of the material found during excavations, which led to the blow in 1884, considering them ultimately responsible, or even because of the missing piles across the entrance. Obviously the financial burden of additional costs was considerably aggravating the situation. Whatever the reasons, the subsequent lack of continuity in key personnel and delays regarding attempts to both fund the project and employ another contractor to complete the works were having significant impact.

Based on earlier comments by Wilson, although it seems that water was virtually ready to be shut-out of the lock once more, the persistent doubts of NHC, undermining the remedial proposals of their own engineers regarding the security of the lock and of course finances, prevented this crucial step being taken. Lewis reported on 9th October, that the lock was silting-up at the rate of about one foot per month, providing details of a comprehensive maintenance schedule he had already reviewed with an independent local assessor. It was agreed to implement the recommendations. NHC finances were now at such a parlous state that even the due payment of £450 (*£59,000) to the arbitrator would seriously affect the remaining resources and they requested that it be paid in instalments.

Yet again, NHC wanted a review of the works by their preferred engineer, Charles Hartley but he was once more indisposed. Rendel, figure 25(c), was subsequently recommended and agreed to the task. Following a visit to the works on 22nd October, along with C. Brereton, Rendel reported his findings on 6th November which again made difficult reading for NHC. In summary, his views were:

- Lock works stood throughout on soil completely pervious to water to about 20 feet below the sills, it would bear weight but may be easily disturbed by water under pressure

- Cannot be made safe by driving rows of sheet piling across alone, propose ring of cast iron piles to 20 feet below sills with additional cross-piling at each end of basin to retain enclosed soil

- Walls need to be cut and restored to allow piling, and concrete placed between piles and side walls of entrance and sills

- Cost of piling estimated at £12,000 (*£1,577,000), with amalgamation of most of Brereton’s earlier estimate the total would be £25,000 (*£3,285,000)

- Completion of lock under current plans estimated at £90,000 (*£11,827,000)

- Lock reconstruction recommended, as current depth of sill and basin insufficient for modern steam trade, limit would be 1200-1500 tons burthen thereby excluding much foreign trade

- Advise 400 feet between gates (extra 100 feet) with the lock and sills sitting three feet deeper. Estimated cost of completion for new lock £131,000 (*£17,215,000)

Proposed designs of both the enhanced current design and the reconstructed lock were provided, figure 26 6

Figure 26 Modified plans of lock area by Rendel, 1885 (a) Authorised amended lock works (b) Proposed reconstructed lock.

Following discussion with Rendel, Brereton reviewed his earlier (March) estimate for completion on 6th November, increasing the earlier estimate by about £9,000 (*£1,183,000) to £86,500 (*£11,367,000), agreeing with Rendel that the cost of a new lock would be approximately an additional £40,000 (*£5,256,000). However, he reduced the basic cost on 13th November, to £49,500 (*£6,505,000) should some work, mainly parts of the dredging plans, be deferred. Still, the choice facing NHC was to either raise further money to complete the damaged works, or an even costlier significant rebuild. Whatever the choice, the original remedial plans of Brereton and Wilson were not going to be implemented.

With completion time running-out once more, a Bill 74 was already underway for an extension and to raise more funds, notably including the statement 'To provide that the further sum of money so raised shall be applied to the completion of the partly-constructed harbour works, with or without a new lock and gates at the outer or seaward entrance to the dock…'. The proposal by Rendel for reconstruction was obviously being given serious consideration, hence the indecision.

It was reported in November 75 that shortly after stopping the New Works that a receiving order had been placed against Daniel’s business , the contract for Neath Harbour having been deemed compromised in the August of 1885. Daniel claimed that the inability to pay his debts was due to NHC (and others) having failed to pay him. For example, the NHC agreement to pay Daniel £10,500 (*£1,380,000) in instalments had, by mid-December, resulted in receipt of just £2,000, not the £6,000 (*£789,000) that had been agreed to be paid by that time. Various communications 6 were issued by NHC between August to year-end 1885, informing debenture holders that interest could not be paid as the contractor had been made bankrupt and all work had ceased; further powers would be sought in Parliament to complete the works but meanwhile they would remain on-stop until additional financing was available.

Following discussions regarding the plans of Rendel and comments by Brereton, NHC agreed in January, 1886 to proceed with completion of the lock along with the engineers’ proposed extra remedial measures. Subsequently, Lewis stated in the Annual Report, April, 1886 7 'On 15th July last the Contractor for the New Works stopped all operations, the plant and materials remaining on the ground. The engines and boilers have been attended to at NHC expense, so far as to prevent damage by frost. The materials, in the shape of iron for gates, hydraulics, etc., etc., have remained exposed during the winter. The Works generally have remained in much the same condition as they were when left by the Contractor; but considerable silt has collected in the Lock and New Cut.' As part of the same report, Brereton confirmed that the exposed works had been protected as much as possible and it appeared that no material damage had occurred over the winter. No further new work had been undertaken but it was anticipated 76 there would be resumption in early June. It was recorded in the Annual Report, that all charges relating to the New Works would now be met out of the revenue of the harbour. Costs for the year 1885-6 was £179-6-2d (*£24,000).

Now, over a year since the cessation of work, the seventh Neath Harbour Act, 25th September, 1886 77 extinguished the borrowing power of up to £60,000 from the 1884 Act, to be replaced with a borrowing power of up to £125,000 (*£16,615,000) to meet the newly anticipated needs. On the basis that the earlier £60,000 could not be raised this does seem somewhat optimistic! It was however, firmly believed that this sum would enable the harbour to be completed 6. The amount included the provision of £14,000 (*£1,861,000) for '…constructing restoring and completing any unfinished and damaged works authorised… and in providing apparatus and plant for working the undertaking…for hydraulic machinery and other appliances…' The original Bill 74 for the 1886 Act did not mention any sea damage although when assent was received, the Act stated that '…the seaward portion of the works having suffered serious damage from the sea NHC cannot raise money for restoring and completing the works unless further facilities are afforded them.' The existing time for completion had actually passed when the Bill was raised, so the ensuing Act incorporated another extension of a further four years, backdated from 16th July, 1885 to extend to 1889.

Finances continued in obvious difficulty. By October, 1886 there still remained £8,500 (*£1,130,000) due to Daniel and a necessary extension with his trustees was agreed. Further problems were arising at the works, the silt level in the Cut now about eight-to-ten feet above the bottom. Brereton was asked to comment on the '…desirability of closing the lower end of the New Cut by a temporary dam to prevent further silting or damage.' His reply of 8th October stated that the initial removal of the silt by dredging or excavating would be very costly. Removal by scour would need to be very carefully managed to ensure the silt was carried away without impacting the river channel to the sea. This could be achieved by a temporary dam with sluices to control the scour at a cost of £250 (*£33,000); a simple dam was recommended at a similar cost anyway, if only to prevent further silting. Even though these options were claimed to be highly cost-effective they were not progressed by NHC.

Undaunted by previous and existing financial difficulties, on the 12th October, 1886 NHC requested Rendel to prepare a new specification for the lock based on his proposals of 1885 so as to realise the completion of the harbour scheme and requested him to consider becoming the associated Engineer for the works should they proceed. On acceptance, he was duly appointed as the new Engineer for these works on 8th December, at which point he set about the new plans. Concurrent with these plans being drawn, NHC urgently required the sum of £14,000 (*£1,861,000) to pay existing liabilities of the works, both of those completed and underway, with an additional overdraft of £500 (*£67,000) being sought to cover ongoing maintenance and protection of the existing works. Inactivity on-site regarding any progress with the works continued into 1887.Early January, 1887 Rendel was in discussion with Messrs. S Pearson & Son [George Pearson & Weetman Dickinson Pearson (Son)], 1 Delahay Street, Westminster, London to become the new contractor to carry out his plans. He was under instruction from NHC to obtain payment terms involving maximising payment in bonds to minimise cash outgoings. During February, although it appears alternative tenders had been sought for the contract, it was agreed to go with Pearson. Costs for the existing works were still being accrued as shown in the extract from the 1886-7 accounts, figure 27 6, in this case amounting to £758-16-2d (*£102,000).

Figure 27 Accounts from 1886-7 showing ongoing costs associated with the New Works.

By mid-1887, it was reported 78 that all capital had now been spent and a new loan was proving difficult to obtain, with NHC responding that work was definitely to restart, although no date was provided. In June, 1887 NHC launched a 5% mortgage scheme offering £100 (*£13,000) debentures 7 in search of the necessary £125,000. The prospectus stated 'The NHC have consulted Sir AM Rendel…under his advice a provisional Contract has been entered into with Messrs. S. Pearson & Son…to complete the new Dock within 2 years from commencement for the sum of £62,400 (*£8,391,000), under the supervision and to the satisfaction of Sir A.M. Rendel , who estimates the total cost of completion and equipment at £90,000 (*£12,102,000).' This sum included all necessary hydraulics, equipment, appliances, etc. to be supplied principally by Armstrong. A comprehensive provisional contract with Pearson was approved on 17th June and stated 7 that the Works were 'more or less completed'. Included were the not insignificant additional cast (or wrought) iron piling work proposed by Rendel in 1885, i.e. around all the works forming the entrance basin and sills, with concrete then to be placed between the piles and side walls of the entrances and sills, figure 26(a). Amongst the still outstanding equipment elements was that of the draw-bridge over the Cut, noted as 'Machinery of Drawbridge, consisting of Lifting Machinery, Screws and Wedging at Overhanging End, Opening Gear, etc., Crabs & Chains' at a cost of £150 (*£20,000). The balance machinery for the draw-bridge remained to be supplied by the Phoenix Iron Co. for £890-0-7d (*£120,000).

Rendel would also be the new arbitrator for the contract, with NHC having six months to place the formal order with Pearson, after which, if nothing was received, the contract could be nullified. Rendel also announced that while he was prepared to oversee the work he was not to be held responsible on completion, as the initial plans etc. were not of his origin. By 18th August, only £6,500 (*£874,000) in applications had been received; there was urgent need to push for more as this was obviously nowhere near the £125,000 required. The total applications received by early November, had still only reached £8,466-13-4d (*£1,139,000). As a next step, NHC considered that if the sum of £20,000 (*£2,689,000) was raised then there was a reasonable chance of borrowing the remainder from a financial institution and reduced the target accordingly. The lack of finances relating to the scheme meant that as no interest had been paid since 1885, a Receiver needed to be appointed by NHC to attend to the arrears; Lewis was appointed as Receiver on 13th January, 1888. Ongoing costs 6 of the ‘New Works’ for 1887-8 were £919-18-6d (*£122,000), thus continuing to drain resources.

The end of May, 1888 saw emphasis continue with attempts to get Pearson to further maximise payment in bonds, the same pressure being applied to Armstrong, Vernon & Ewens, The Phoenix Foundry Co., Daniel’s trustees and any others requiring payment. At the same time concern was increasing over the state of the works, Lewis stating 'The plant left on the New Works is deteriorating considerably in value and must continue to do so in its present exposed position, subject to the influence of Sea Air. I would recommend that if practicable a certain portion not likely to be again required on the Works should be sold or otherwise disposed of before next Winter.' Payment terms for the major suppliers had been agreed by 5th September, Pearson would accept £30,000 (*£3,988,000) of the contracted £62,400 (*£8,294,000) in bonds, although some significant compromises on plant ownership and cash availability were conceded by the NHC, with the balance in cash; Vernon & Ewens would accept £1,700 (*£226,000) in bonds and £300 (*£40,000) cash, Daniel’s trustees £8,000 (*£1,063,000) bonds and £500 (*£67,000) cash, Armstrong £9,000 (*£1,196,000) in bonds. In light of these arrangements, the NHC believed that the potential for further borrowing was very favourable. While no evidence has been found that these cash payments were made, it is likely that at least the respective bonds element would have been paid in full.

Time continued to pass such that the eighth Neath Harbour Act, 9th July, 1889 79 requested another extension of time to completion for a further three years, to 28th July, 1892. Also, borrowing power was now at £137,500 (*£18,069,000), having increased by £12,500 (*£1,643,000) to cover costs associated with small debts, and £10,000 (*£1,314,000) for appointing the Receiver. However, on 23rd June, NHC were discussing the decision of the bank of Sir Samuel Scott declining to take-up the raising of the funds, leaving the whole issue of financing floundering once more. To avoid any cash outgoings, Pearson was to be asked to take on all costs associated with the other major suppliers, for a total payment of £100,000 (*£13,141,000) in bonds. If this was declined then NHC would seek another contractor.

Meanwhile, during July, NHC agreed to seek an independent view as to the prospects of the harbour once the works were completed with a subsequent report prepared by 'two dock experts'. These were Mr. Foster Brown of Cardiff, who apparently had extensive local knowledge, and Mr. George Raymond Birt, (1830-1904), General Manager of Millwall Docks, London figure 28 80 (Birt was to later have financial issues with the accounting of his own business hence the nature of this portrait).

Figure 28 George Raymond Birt, General Manager, Millwall Docks, London, submitted a joint report on the future of Neath Harbour, 1890

Their findings were reviewed by the NHC along with both Robert and Cuthbert Brereton, on 20th February, 1890 and yet again gave cause for great concern, including:-

- Completing the harbour as originally planned would not be suited to modern trade requirements

- With 17 feet on the sill and need for a two feet margin, the 15 feet potential would restrict vessels to about 500 tons at mean neap tides. Swansea could accommodate this and greater without having to wait for increased tides

- To benefit from long-distance transport some optimum vessel sizes were now even larger, e.g. 800-1500 tons, and would have limited access to the dock as dictated by tides

- Whilst the harbour is ideally positioned for large trade and will have suitable water area and frontage, this trade will “…never offer itself with a lock limited, at times, to 17 feet…” - the lock sill should therefore, now have 22 feet of water over it not the original 17 feet, with associated work necessary on the channel to the sea

The report was subsequently passed to Robert Brereton and Rendel, for comment and costings on these potential necessary improvements. Basically they were to '…remodel the Works of the present entrance…' to allow an increase of five feet at sill and accommodate increased length of vessels, the outcome being:-

- Lock-basin 400 feet long and 55 feet wide at gates, with 22 feet of water at its sills on high-water of mean neap tides - £35,000 (*£4,599,000)

- Deepening of Entrance Channel - £45,000 (*£5,913,000)

- Further works and facilities in the float - £10,000 (*£1,314,000)

- Contingencies - £10,000 (*£1,314,000)

This meant that a further £100,000 (*£13,141,000) would be needed in addition to the already sought £125,000 (*£16,426,000), which so far was itself proving very difficult to obtain. On 19th May, Lewis issued a note to existing bondholders explaining that due to the attempts at funding over the previous year proving unsuccessful, NHC had reviewed the situation with independent experts and that revisions to these earlier plans were now underway. Separately, NHC agreed that costs associated with these new plans would be in excess of current (failed) borrowing and they would need to reassess their financial position. The following month it was agreed to accept the new scheme as proposed by Brereton and Rendel, authorising the raising of the necessary capital.

In August, 1890 81 the ongoing situation of the harbour was described at a Neath & Brecon Railway Company meeting. Their chairman, Sir Edward Watkin, believed the future of the floating dock was one of having little hope, claiming that with NHC having spent £375,000, the harbour was now as good as abandoned, adding he had never experienced in his life anything as wretched as the condition of the harbour. Another member’s comment described the project as one of the most melancholy instances of financial failure that he had ever met with and he had '…a regular attack of the ‘blues’ after seeing the works.'! Ever-onwards, NHC raised a new Bill in the October which was deposited early 1891, to further extend the period of completion. In March, 1891 NHC acknowledged that following the 1886 Act, the efforts to raise the monies identified as necessary to complete the new harbour had failed 6. Also, since the time of the original plan for the harbour in 1874, modern needs had changed, hence the need to increase the borrowing to £250,000 (*£32,852,000). It is notable that even in June, 1891 the means of obtaining the appropriate capital had not been agreed. The further £125,000 borrowing power sought in addition to the £125,000 that NHC were empowered to raise in 1886, (which of course had already failed) was to be incorporated into the next Act of 1891.

The ninth Neath Harbour Act, 9th July, 1891 82 again extended the completion date of the works. This was in advance of the already underway three years permitted from the previous 1889 Act date of 28th July, 1892, to a further two years from the date of the ninth Act, to 28th July, 1894. Also incorporated was the extension of three years to the same date for the 1884 Act, regarding the diversion of the Cwrt Sart Pill, which had now reached expiration. NHC intentions, were as stated in the Bill 83 '…restoring, altering, improving and completing the partially destroyed lock and entrance basin to the Harbour or float…' although other aspects of the Act basically allowed the project to be abandoned should it be deemed appropriate e.g. 'To authorise and empower the NHC to sell, or to demise and lease the whole or some part or parts of their whole Undertaking.' The Act itself stated '…since the harbour works were authorised in 1874 the tonnage and draught of water of vessels employed in the carrying trade have been greatly increased and it is expedient that the depth of water at and near the entrance to the harbour and the dimensions of the lock and entrance basin should in the course of restoration be also increased in order to admit of such larger vessels entering the harbour…' in-keeping with the revised aspirations. Unsurprisingly, the aim to borrow this new, increased total of £250,000 yet again proved futile.

4.4.1 Other Projects Impacting on Neath Floating Dock

It is worth noting that while the Neath Harbour project was being implemented; other bodies had concurrent interests of their own in the area. To take full advantage of the increased (mainly) commercial and passenger railway traffic, by reducing transport costs, since the 1840s various plans were presented for a railway line from the Port Talbot direction to Swansea crossing the river by bridge at Briton Ferry, bypassing Neath. These were invariably objected-to by NHC on the basis of potential interference with river traffic. However, so determined were the promoters that work had begun in 1883, by the RSBR, following their Act of 2nd August, 1883 which included a tunnel under the river, located towards the mouth of the estuary. Whilst considerable progress was made, this challenging endeavour was halted in 1885, initially due to financial problems but also for geological reasons, finally ceasing in 1886 6.

Nonetheless, pressure for a crossing continued and eventually, via their RSBR Act, 27th June, 1892 84, RSBR were granted permission to build a railway from Port Talbot to Swansea incorporating the building of a swing-bridge over the river, thereby reducing the line distance between Cwmavon and Swansea by about seven miles 85. This Act not only involved the building of a swing-bridge over the river but also '…to appropriate and convert to purposes of their intended Railway…including the Bridge intended to carry the same over the authorised Navigable Cut…' i.e. using the already partly-constructed railway and embankment. As part of the NHC terms, who still had no intention to give-up on the harbour plan, the original draw-bridge over the Cut was duly incorporated into the 1892 Act '…over the navigable cut shall have an opening span of not less than 50 feet in clear width…capable of being opened and closed for the passage of vessels.” RSBR would “…use the bridge of the commissioners over the navigable cut and shall complete it at their own cost…' It would be reasonable to assume that the draw-bridge was close to, if not completed, at that time, with the likelihood of relatively little further work required. Whatever, it was now the responsibility of RSBR to ensure it was in working order to allow opening when and if needed, as part of the agreement with NHC. Figure 29 10, shows the swing-bridge across the river (left), and a bridge at the location of the planned draw-bridge across the Cut (right). The three piers of the original draw-bridge are clearly seen traversing the Cut.

Figure 29 Aerial view showing swing-bridge at centre of river and the three piers of the draw-bridge over the navigable Cut (undated)

The building of the hydraulically-operated swing-bridge over the river was a massive undertaking. Construction began in 1892 and on 18th August, 1894 the finished bridge was first successfully “swung by ropes” as a test 86, by just two men using a crab winch 87. The line was opened on 9th October, 1894 88 and at that time was the only swing-bridge in the UK to be built both on the skew and on a curve.

4.4.2 Beginning of the End for the Neath Floating Dock

Returning to the harbour scheme, an update on the future of the Neath floating dock, late November, 1892 gave mention 89 to strong rumours that a syndicate had been formed in London and all monies required for completion of the harbour was available but this proved to be yet another false dawn. The next year 1893, saw little, if no activity regarding the floating dock apart from the deposition of the next Bill which would seek another extension of the time to completion. The remaining plant and materials on-site were inspected during May, 1894 with comprehensive assessments given by C Brereton and Lewis. RP Brereton died 1st September, 1894 and it appears Cuthbert had at some point already taken the role as NHC Consulting Engineer. It was reported that some items had suffered significant deterioration over the last 10 years or-so, with the advice being that following the ongoing routine maintenance, to clean and paint those items worst affected. The lock gates were particularly corroded, the HEH roof was leaking and during high spring tides, water was getting into the HEH basement. NHC agreed to the additional work. In the lead-up to the passing of the proposed 1894 Act, the condition was described 90 as having '…been in a moribund state for several years…which are now a sad scene of wreck and desolation.' The tenth Neath Harbour Act, 3rd July, 1894 91 extended the time to completion of all works for a further three years, to 28th July, 1897. Due to the lack of ongoing work regarding the harbour, the Cut was continuing to silt-up 92, the ebb and flow of the river from the Briton Ferry end since the breach in 1884, continuing unabated.

During 1895, the cost of removing the lock and associated dredging was now being considered. A joint report by C Brereton and Lewis was provided on 4th November, regarding both lock removal and an assessment of materials on-site e.g. bridge girders, hydraulic machinery, iron in gates, capstans and crabs, etc. Many items would need repair or renewal, e.g. gates, to meet the requirements of the most recent plans. Basically, they had concluded that the lock having been designed about 20 years earlier was now unsuitable, needing to be removed and rebuilt. Lock removal was estimated at £10,000 (*£1,345,000). NHC reviewed these findings and agreed to seek funding to undertake the recommendations. In July, 1896 NHC agreed that an application would be sought to extend the time for completion once more, the aim being that this would be an updated and ‘final’ scheme. The works needed to be seen through to some form of completion since, if they were simply abandoned, NHC would be liable if there was any subsequent impact on trade through the Temporary Channel. NHC would be forced to remove any obstructions to navigation whatever happened. Figure 30, from 1897 93, shows the lock virtually intact although effectively the Briton Ferry side is an island, the river course continuing as the Temporary Channel; the whole of the works area are designated ‘sand and mud’.

Figure 30 OS map 1897 (a) Showing the lock area designated ‘sand & mud’, the navigable Cut being open at the Briton Ferry end (b) Condition of embankments and tramways etc. including tramway passing the HEH

The Temporary Channel and its navigation protocols were still in place during 1897 7, also the causeway built for the terminus of Railway No.2 was by now breached as indicated by ’mud’ at top of figure 30(a). The state of the works on the marshlands, i.e. embankments and tramways, are shown in figure 30(b). While the tramways mirroring Railways No.1 and No.2 are clearly shown, with a tramway also running past the HEH, river embankment breaches are evident.

Despite earlier intentions of finality, the eleventh Neath Harbour Act, 3rdJune, 1897 94 was raised simply to obtain an extension of the time to completion of a further three years of all works, now to 28th July, 1900.Although no perceivable work was being undertaken, NHC remained resolutely determined to continue to ensure there would be no impediment of river navigation to Neath, either along the river or through the navigable Cut. A plan proposed in 1898, by the Neath, Pontardawe and Brynaman Railway Company where a section of their proposed railway would terminate at a junction near/on the Cut draw-bridge was successfully opposed. NHC had not given-up quite yet.

REFERENCES FOR PART FIVE

74. The London Gazette 27 November 1885

75. The Western Mail, 13 November 1885

76. Weekly Mail, 22 May 1886

77. 'An Act to confer further powers upon the Neath Harbour Commissioners to alter the constitution of the Commissioners and for other purposes', Neath Harbour Act, 25 September 1886

78. South Wales Daily News, 2 June 1887

79. 'An Act to extend the time for the completion of the authorised works for enlarging and improving the Port and Harbour of Neath and for other purposes', Neath Harbour Act, 9 July 1889

80. Police Gazette, March 1899

81. South Wales Daily News, 20 August 1890

82. 'An Act to extend the time for the restoration and completion of works for enlarging and improving the Port and Harbour of Neath to confer further borrowing powers upon the Neath Harbour Commissioners and for other purposes', Neath Harbour Act, 9 July 1891

83. The London Gazette, 21 November 1890

84. Rhondda and Swansea Bay Railway Act, 27 June 1892

85. South Wales Daily News, 13 March 1891

86. The South Wales Daily Post, 20 August 1894

87. South Wales Echo, 29 August 1894

88. South Wales Echo, 9 October 1894

89. The Western Mail, 28 November 1892

90. The Cambrian, 4 May 1894

91. 'An Act to extend the time for the completion of the authorised works for enlarging and improving the port and harbour of Neath', Neath Harbour Act, 3 July 1894

92. The Glamorgan Gazette, 9 November 1894

93. OS 1897, National Library of Scotland

94. 'An Act to extend the time for the completion of the authorised Works for enlarging and improving the Port and Harbour of Neath', Neath Harbour Act, 3 June 1897

END OF PART FIVE

PART SIX

4.5 From Public Auction to Lock Removal, 1899-1908

Significant maintenance costs continued to be incurred by NHC, who recognised such that the tolls placed on shipping were insufficient. Subsequently, during June, 1899 NHC agreed that all perishable materials and plant should be sold by public auction, to include the hydraulic engines, boilers, HEH and the bridge over Tennant’s Canal. Now that it had been decided to sell-off what remained, figure 31, any realistic hopes of completion were ending.

Figure 31 Details of public auction for remaining materials and equipment associated with the ‘Neath Harbour and Docks Contract’, 1st-2nd August, 1899 95

The auction realised about £4,600 (*£605,000) nett, which NHC considered a satisfactory amount. At the same time, tenders had been sought and received for the removal of the lock but were in excess of £20,000 (*£2,628,000) and not considered as giving a satisfactory return. Hence, a request was made to C. Brereton for a report on the possibility of immediate improvement of the Temporary Channel at a suggested cost of £3,000-£4,000 (*£394,000-£526,000). The findings were presented to NHC during October and it was agreed that a tender for the work should be sought. Also, a revised lock removal scheme was proposed by Lewis, to remove only the east side of the lock, for which tenders would also be invited.

NHC agreed on 20th October, to raise another Bill which would include the option of abandoning the works, selling certain lands, reduce and cancel existing borrowing powers and create new powers to borrow £20,000 (*£2,628,000) for works yet to be named, almost certainly lock removal. The reduction of capital from the original £370,000 (*£48,621,000 in 1899) to £37,000 (*£4,862,000) was also mentioned, although the mechanism was not incorporated. During discussion of the Bill the following statement was made96 “The commissioners since a serious accident which happened in 1884 had come to the conclusion that it was hopeless to attempt to make a big concern of this undertaking and to carry out any large works. Still, a good deal of trade would be done if there was a good navigable channel made into the dock. The object of the Bill was to obtain powers to borrow £20,000 simply for the purpose of putting themselves straight with regards to the accident and requirements of navigation. So far as this Bill was concerned, their existing powers to borrow £250,000 were abandoned.” The Bill itself stated 97 “…for the purpose of facilitating the access thereto from the sea, and to abandon, remove, alter or reconstruct the constructed lock, and other authorised and partly constructed works which are or may become an impediment to the navigation, and to improve the authorised and existing river wall, embankment and training walls…” and “…to authorise NHC to abandon and relinquish the construction or completion of the existing partly-constructed harbour works...”. The further borrowing of £20,000 (*£2,514,000) was essentially sought to complete these works and “…wipe out all arrears of interest due on the £370,000…” 98 So, NHC proposed to ensure all obstructions to navigation were removed, basically, do all that was conducive to facilitate ongoing shipping business. Effectively, the ‘completion’ was simply making a “…good navigable channel into the dock…” 99. While the Bill was being progressed, in June 100 NHC even asked Neath Council for assistance to complete the dock or remove the lock but were rather ridiculed in the reply 101 “No doubt the Council would be delighted to give the Commissioners their moral support. (Laughter). ” The subsequent twelfth Neath Harbour Act, 10thJuly, 1900 102 included six key points.

Figure 32 The six key points of the twelfth Neath Harbour Act, 1900 effectively closing the project

This Act proved to be the final request for funds associated with the project and was also the final request for funds to once more fail. Also included, was the arrangement whereby the GWR agreement of 1878 was repealed and the divesting of all aspects of Railways No.2 and No.3 by a proposed selling or renting to RSBR.

Remaining patently obvious was that the remaining obstructive lock would need to be removed and the Temporary Channel replaced by a new navigable channel more resembling that pre-1882. During July, the four tenders received for the next attempt to meet the revised lock removal requirements were reviewed. The contract would basically require all elements at the east side of the lock to be removed down to three feet above sill level and included an increased remuneration for removal of materials below five feet, recognising the enhanced difficulty at this stage of work. NHC agreed to accept a Mr. Taylor’s quote of £15,396 (*£1,935,000), being the lowest of the four, the highest being £20,490 (*£2,576,000). This in-turn, was subject to NHC obtaining a loan of £12,000 (*£1,508,000). Whether it was Taylor or NHC that decided against proceeding is unclear but it appears that the contract was not formally agreed, certainly no certificates of work or comments relating to work by Taylor have been found. The contract for lock removal 7 was subsequently signed by T & A Scott, New Steel Works, Port Talbot, on 19th May, for £7277-9-0d (*£915,000), with a completion time of nine months. Scott was not one of the original four submissions, the tender seeming very low compared with that of Taylor for what appears to be for the same amount of work required. As detailed in the specification, the work was extensive, a part of which is shown below.

Figure 33 Part of specification agreed with Scott for lock removal 1901 – this is a copy of the original that was amended for later use, hence alterations

Figure 33 Part of specification agreed with Scott for lock removal 1901 – this is a copy of the original that was amended for later use, hence alterations

While the lock removal process was underway, the final stages of this unfortunate project were spelled-out in the thirteenth (ironically?) Neath Harbour Act, 2nd July, 1901 103 entitled “An Act To Reduce And Regulate The Amount Of The Debt Upon The Neath Harbour Undertaking”. The Act included the statement “To discharge, or provide for the discharge, of the receiver and manager of the Harbour Undertaking appointed by the Court…”. This was basically an administrative Parliamentary Act necessary for NHC to be extricated from the heavy ongoing debt which had no chance of being paid. No interest had been paid on the initial raised amount of £370,000 since 1885 and existing bondholders were canvassed regarding reducing the value in total to £37,000 (*£4,651,000) which would allow a reduced interest rate of 2.5% p.a. to be paid, rising to a maximum of 10% if revenue increased accordingly. No doubt taking the view that ‘something is better than nothing’, bondholders to the original value of £260,900 agreed to the proposal, with £6,700 in original value dissenting. This agreement allowed the discharge of the Receiver, Lewis. The debt was thereby reduced via this Act to £37,000 and incorporated a procedure for the closing-out of the scheme whereby holders would be paid monies due on their respective mortgages after 20 years. Defeat was acknowledged by NHC and the death knell on this project had, at long last, been sounded 104. All old debts were extinguished and the Neath floating dock scheme officially closed, bar the remaining relatively low-outgoing mortgage scheme e.g. it is known that 2.5% was paid for the year 1902-3.

It was now August, 1901 and there came a report of most unsatisfactory progress by Scott regarding lock removal. The small amount of work completed had included removal of the slag training banks at the head of the lock, figure 15, with the result that the change in scour had impinged and caused damage to the passage forming the Temporary Channel. This needed remedial action by replacing a section of planking that had also been removed. The year 1902, duly arrived and in January, an inspection of the lock removal works by NHC was undertaken. The view was that there was still very little progress, with an estimate of only about 1/10th of the contract having been completed and only about two months of the contracted time remaining. Scott blamed his own contractors (headed by his brother) for the poor progress and explained he had now “…got rid of his brother as a partner…”, although it was unclear which brother led the company. Scott “…begged the Commissioners to take into consideration his unfortunate position on account of his brother’s conduct in not proceeding with the work…” and was given one month to demonstrate significant progress. Less than two months later, the contract was terminated due to ‘financial difficulties’ associated with Scott’s inability to proceed. Maybe after all, his very low initial tender was too good to be true.

The Harbour Authorities’ report 1903 105, regarding the activities at UK harbours over the past 20 years, included the contribution of Neath Harbour, stating that the Engineer in charge was indeed now C. Brereton and that the depth of water through the works at low water was at that time, “…a running stream…”. The NHC Annual Report 1903 7, stated “Nothing further has been arranged in connection with removal of the remaining portion of the Lock, but as the work done by Messrs. SCOTT has made the navigation somewhat easier at this spot, the matter does not appear to be so urgent.” This lack of urgency and no doubt finances, meant that work to remove the lock was to remain in further abeyance for about five years. It seemed that while NHC could not get the lock completed since the 1874 Act of 30 years previous, they now could get what had been constructed, removed. It was mentioned 6 that the Main Colliery Tide Table 1905, warned of some obstructions in the channel between their wharves and Red Jacket Pill although the Temporary Channel remained useable. By 1907-8, Lewis had become a Harbour Commissioner, with the Harbour Manager (Superintendent), and Works Engineer, now C. Drew Godfrey and B. Branfill, respectively. Although it appears tenders for the lock removal had once again been sought and received during 1907, applications for alternative tenders to remove the lock and restore the channel were once more requested during February, 1908106.

Figure 34 Advert regarding tender for Neath Harbour lock removal, etc., 1908

The specification for the lock removal etc. of 1901, as signed by Scott, figure 33, was revised, the main portion of the work required now shown in figure 35, illustrating both the remaining structures and their substantial remaining supporting banks, although it appears that the entrance lock east side had lost part of its top structure by this time. This contract now required the lock structure in the river to be removed down to five feet above the sill, not three feet as previously specified. This would of course reduce costs.

Figure 35 Area showing remaining sections of lock for removal (a) Plan view of lock and slag training banks (b) Sections 5, 6, 7 referenced in figure 35(a)

Following a review, NHC awarded the contract to George Palmer, Neath for £5,009 (*£616,000), figure 36 7 which was duly signed on 9th March, 1908. On acceptance of the tender, on 10th April, ‘The Main Colliery Company, Ltd.’ confirmed a previous agreement whereby they would provide an interest-free loan of £1000 (*£ 123,000) to NHC once £4,000 had been spent on removal of the lock, repayment being monthly against their toll account.

Figure 36 Contract for lock removal as awarded to George Palmer 9th March, 1908

The contract period was six months, commencing 28thApril. Basically, everything five feet above sill level that would potentially impede the revised dimensions of the new (restored) navigable channel was to be removed. The specification included removal of the substantial amount of materials remaining in the backing to the east wall, figure 35(b). The previous contract with Scott in 1901, had also included the final item “Deduct value of timber, ironwork, etc’ at a rating of £250 (*£31,000)”. The new contract rated these items at £10-15-0d (*£1400), for no apparent reason with no work having been undertaken meanwhile, unless significant amounts of materials had been systematically removed during the intervening period. The work at the lock was reviewed on 26th November but NHC were informed that six more weeks would be needed due to a lack of available labour. The combined prospects of working tidal and night-work was apparently keeping men away; despite Palmer increasing wages, a number of nearby alternative projects were ongoing, resulting in this dearth of manpower. However, most dredging was complete with only about a further one foot in depth required. Also, extra work was necessary due to some unrecorded walls not included in the contract.

Late April, 1909 saw the lock removal and restoration of a new navigable channel work completed, lights and signalling protocol in the Temporary Channel having been discontinued on 1st March. In June, NHC agreed to full payment for Palmer, with no penalty for lateness being enforced, the final cost being £5550-2-8d with the contract overage covered by a 10% contingency. It was recommended by Branfill that regular checks were adopted to assess the new channel flow and that it was being scoured correctly. The Briton Ferry (east) side section of the lock is no longer seen by 1913, figure 37(a) 107, the navigation channel now running more central along the river, past the lock entrance and continuing upriver. The absence of tramways etc. following the sale of all associated materials held in 1899, is apparent in figure 37(b) 108 from 1914 when compared with figure 30(b) from 1897.

Figure 37 OS maps showing river area post-lock removal (a) 1913, showing absence of lock structure on Briton Ferry side (b) 1914, with absence of tramways in the original works area following auction of materials in 1899.

5.0 Resurrection of the Floating Dock, 1908-1918

A couple of relatively fallow years regarding any harbour developments ensued but ever-looking-forward, in late 1910, NHC requested an assessment on the ability of the harbour to accommodate vessels of 2000 tons burthen. The outcome was reported by Sidney H. Davey, General Manager, Neath Harbour Offices, in January, 1911 and included a section regarding the use of remnants of the west lock wall. It was estimated that to make that area alone viable, would incur a cost of £4,856-15-0d (*£585,000), with approximately 1/3rd of that cost associated with removal of the masonry of the cross-wall remnants on the river bed. It was not progressed. However, the Act of 1901 was not the conclusion of activities associated with a new Neath Harbour, the idea of a floating dock for Neath still lingered-on. Towards the end of 1911, assuming a request had been made although none found, RSBR were informed that if they wanted to replace the existing draw-bridge over the navigable Cut with a fixed span, then they could proceed. However, they would need to undertake the re-conversion at their own cost should the Cut need to become navigable as per original plans, requiring an opening span. No further information has been found regarding this matter hence, it is not known if the one-piece retractable centre-section was replaced at that time.

During 1912, a report was commissioned from Sir John Wolfe-Barry (figure 25a), Lyster & Partners (J. Wolfe-Barry, Anthony G. Lyster, E. Crutwell, K. A. Wolfe-Barry), to consider ‘Dockizing’ the navigable Cut; notably, Barry had worked in partnership with I.K. Brunel’s son Marc, since 1878 and was a business partner with C. Brereton. Details were discussed on 12th October, whereby it was agreed to commission further work by Barry et al, for the “…dockizing of the river itself and retaining the Navigable Cut as a Cut.” A plan for a new “Neath Dock Scheme” was reported in 1913 109 boring operations being undertaken as part of the assessment for suitable foundations. The initial plan for dockising the river, proposed in 1913 7 figure 38, involved impounding the river via the earlier proposed embankment while largely retaining the course of the associated railway over the dam. This approach would utilise some of the work already undertaken as part of the earlier scheme, reducing costs. The proposed distance between the mitred lock gates was 325 feet at a width of 60 feet, leading to the 400 feet-long x 450 feet-wide turning-basin.

Figure 38 ‘Dockizing’ proposals 1913 (a) Lock and basin area (b) Lock details (c) Embankment across river

Following these proposals, in June, 1914 NHC commissioned a report from Barry et al, to consider “…the question of improving the Harbour above Briton Ferry to meet modern requirements.” Further surveys of the river up to Neath bridge were undertaken 110 with a final report and plan produced 7 figures 39, 40, on 17th July, 1914.

Figure 39 New plan of Neath Harbour by Barry et al, 17th July, 1914

The report noted that in 1906, over 600 vessels shipped approximately 300,000 tons of coal from Neath Abbey Wharf alone, with coal shipments still increasing. However, despite all previous improvements to the navigation channel over the years, no vessels over 4000 tons burthen could enter the harbour. Two options were provided in the report. The first was so as to meet current needs, the second aiming to meet potential future requirements. The former comprised a lock, now increased to 875 feet between inner and outer gates, at 90 feet wide, with a middle set of gates – to both save water and for safety - to give an inner length of 525 feet.

Figure 40 Enlarged lock area of ‘Dockisation’ scheme from 1914, dotted lines showing future potential developments

The river would need to be deepened and widened up to the swing-bridge, the Cut again being used as a navigable channel, marshlands either-side of the Cut and river would be reclaimed by depositing sand and rubbish from the river bed, with the major changes compared to the previous scheme of 1874, occurring downstream of the basin. The Cut now began nearer to Giants Grave i.e. further downstream than previous, this section now designated ‘New Cut’, at which point the original course of the river led to the series of locks which served a substantial ‘Turning Basin’ incorporating two graving docks. The railway, originally Railway No.1 of Brereton, was now proposed to be a dedicated line running along the original route from the Neath Abbey area of the river. It would then run across the impounding basin embankment dam to serve firstly both the graving docks, then running past the large ‘Turning Basin’ to terminate between the lock and entrance to the modified new Cut. A second railway line was proposed with a take-off on the Skewen side, running alongside Tennant’s Canal to terminate at virtually the opposite side of the basin to the Neath line, while providing a link to the RSBR. A second ‘opening bridge’ was proposed at the new Cut entrance to link with a ‘New Road’ from Briton Ferry with the lock. Scope for increasing the lock size in the future, should it be required, was also indicated as shown by the dotted lines shown in figure 40. This was to include a second lock at the west bank side, 1000 feet long x 100 feet wide i.e. as Newport at that time.

The estimate, not including the graving docks or roads, was £872,000 (*£102,896,000), with the assertion that the docks could be completed by 1920. The ‘basic’ scheme was reported 110 to be well-financed and there was high confidence that it would proceed despite the initial costs being stated as in excess of £1m (*£118,000,000), with estimated costs 111 at £2m (*£236,000,000) for the larger scheme. However, the outbreak of the Great War resulted in the project being suspended. Nonetheless, hopes remained even in 1917, when a proposed bridge over the river at Briton Ferry was linked with the “…dockisation…” project 112. On 6th June, 1918 NHC agreed for a ‘reduced’ dockising plan to be prepared for consideration. The annual NHC meeting on 13th June, 1918 agreed to defer the plan 113 ultimately shelving current hopes and plans of a floating dock for Neath, there being no resurrection of the plan following cessation of wartime hostilities. Well, nearly. Even in 1919, when yet again, the idea of the latest river-crossing bridge scheme at Briton Ferry was being discussed 114 Barry was called as a witness, claiming that if the bridge went ahead then “…it would bar forever the development of the scheme for the dockisation of the river which his firm was consulted upon in 1914.” The bridge did not proceed but it does seem it really was the end of plans for a Neath Floating Dock. Yes, this time it really was.

While it was certainly the end of the plans, the outstanding mortgage debt that had been revamped in 1901 was still being borne by NHC in the form of annual interest. Limited financial reports show the following interest payments: 1914 – 3% with £370 (*£44,000) set aside for the purpose of reduction of bonds 115 1916 – 2.5% 116 1918 – 0% 117 1919 – 2.5% 118. Records show that in 1918 119 NHC decided to withhold interest payments, so even this 2.5% interest on the £37,000 was therefore, periodically proving difficult to find as trading conditions varied. Ever looming was the repayment of mortgages to holders due in 1921 but for reasons not found, probably as unaffordable by NHC, this did not occur.

A press report 120 on a Parliamentary Select Committee sitting on 21st July, 1924 to consider the next Neath Harbour Bill stated “It was sought to enable the NHC to put their harbour in order. They had been short of money for many years and the harbour had fallen into a bad condition. There had not been sufficient revenue coming in to enable them to maintain it in proper condition year by year and it would be necessary to spend more money for the purpose than had been expended for many years past. The Harbour Commissioners were also hampered by a debt which was created in the last century. They had been unable to pay that debt except to a very small extent and the Bill was designed to enable them, out of revenue, to put by sufficient money to pay off their debt by the year 1941.”

The resultant fourteenth and final Neath Harbour Act, 1st August, 1924 121 although principally raised to allow increased tolls, also incorporated an extension of the mortgage scheme by a further 20 years, to 1941. Interest continued to be paid when available and further monies may have been set-aside as in 1914, although the amounts for the latter cannot be confirmed. It appears that 1941 did not see the complete drawing of the mortgage debentures, probably due to the ongoing war situation. In 1970, what appears to be a final action of the scheme was initiated. While it is not known how much money had been set-aside in total for mortgage payment up to that point, notices were given 122,123 to all undrawn debenture holders that a ‘Drawing of Mortgage Debentures’ issued under the Neath Harbour Acts 1874-1924, would be held on 2nd April, at the Gwyn Hall, Neath. A follow-up notice was made 124 listing those debentures remaining undrawn after the earlier session. A second ‘Drawing’ notice was made in 1971 125 for 1st April, at the Harbour Offices, 3 Bethel St., Briton Ferry probably to complete the earlier exercise. No further notices have been found detailing any remaining undrawn debentures, hence it is surmised that nearly 100 years after commencement of the scheme via the Act of 1874, with the mortgage scheme now settled, at long last, all aspects of the Neath Floating Dock were concluded.

REFERENCES FOR PART SIX

95. South Wales Daily News, 22 July 1899

96. The Western Mail, 3 May 1900

97. The London Gazette, 21 November 1899

98. South Wales Daily News, 30 December 1899

99. South Wales Daily News, 3 May 1900

100. The Cambrian, 8 June 1900

101. The South Wales Daily Post, 8/6/1900

102. 'An Act to confer upon the Neath Harbour Commissioners further powers for the improvement of the Harbour to reduce and regulate the indebtedness and borrowing powers of the Commissioners and for other purposes', Neath Harbour Act, 10 July 1900

103. 'An Act to reduce and regulate the amount of debt upon the Neath Harbour Undertaking and for other purposes', Neath Harbour Act, 2 July 1901

104. Evening Express, 28 December 1900

105. Harbour Authorities Reports, House of Commons, 1903

106. Neath Gazette Mid-Glamorgan Herald, 22 February 1908

107. OS 1913, National Library of Scotland

108. OS 1914, National Library of Scotland

109. The Cambria Daily Leader, 8/10/1913

110. Herald of Wales and Monmouthshire Recorder, 27 June 1914

111. The Cambria Daily Leader, 10 July 1914

112. The South Wales Daily Post, 17 November 1917

113. Llais Llafur, 15 June 1918

114. The Cambria Daily Leader, 25 March 1919

115. The Cambria Daily Leader, 27 May 1914

116. The Cambria Daily Leader, 21 June 1916

117. Llais Llafur, 15 June 1918

118. The Cambria Daily Leader, 28 May 1919

119. Llais Llafur, 19 June 1918

120. The South Wales Daily Post, 22 July 1924

121. 'An Act to alter and increase the rates tolls and dues leviable by the Neath Harbour Commissioners and for other purposes', Neath Harbour Act, 1 August 1924

122. The London Gazette, 30 January 1970

123. The London Gazette, 17 February 1970

124. The London Gazette, 12 June 1970

125. The London Gazette, 23 February 1971

END OF PART 6

PART SEVEN

4.4 Fro

6.0 Neath Floating Dock - Aftermath

All remnants of the abandoned works that had been either completed or partially completed by the start of the Great War were thereafter, left to the mercy of the elements. However, parts of the scheme remained visible for some time after the closure of the project and indeed some are still to be seen to this day.

6.1 Hydraulic Engine House (HEH) and Railway Embankments

The HEH, figure 23, was constructed between the Cut and the river. Despite being completed, due to the ongoing issues with harbour construction the purchased hydraulic apparatus and pumping equipment remained unused prior to auction in 1899. The remaining structure of the HEH outer shell looked forlorn for many years, figure 41(a)-(h) and was colloquially known as the ‘Chapel on the Marsh’, until its demolition in the 1990s, figure 41(h). The stone was then removed and used on the Dulais River at Aberdulais Falls to rebuild the walls controlling the water flow.

Figure 41 The abandoned, unused Hydraulic Engine House (HEH) (a) Shown between the river and navigable Cut 64 (b) At high tide 126 (c) View from riverside6 (d) View from downriver 10 (e) View from riverside 126 (f) View from Cut side 126 (g) View inside HEH showing equipment bed126 (h) Demolition in 1990s 6

Figure 41 The abandoned, unused Hydraulic Engine House (HEH) (a) Shown between the river and navigable Cut 64 (b) At high tide 126 (c) View from riverside6 (d) View from downriver 10 (e) View from riverside 126 (f) View from Cut side 126 (g) View inside HEH showing equipment bed126 (h) Demolition in 1990s 6

Figure 41(c) shows the taller freestanding boiler stack sitting in front left of the boiler-house, the squat accumulator tower alongside in front of the engine-room, with figure 41(g) showing hold-down bolts on the bed of machinery inside the engine-room. Prior to the demolition of the HEH and before the domestic refuse tip covered much of the Briton Ferry side of the Cut area, the remains of Railways No.2 and No.3 approach bank could still be seen, figure 41(b), running towards the HEH, with the ever-encroaching refuse tip looming behind.

The original route of Railway No.1 prior to joining Railway No.2, running from Neath to the river where it was to cross the dam of the initial impounded basin can also be seen, figure 2(b) and is readily observable when travelling over the river bridge from Windsor Road, Neath, to the A465 as a distinct raised embankment beginning at the entrance to the marsh off the A465 roundabout. This embankment is marked by telephone poles and vegetation along the relatively barren marshland. Apart from this embankment and the remnants of the Cut on the Neath-side, the features shown in figure 41 are largely obscured by the landscaped refuse tip.

6.2 Navigable Cut

A GWR map of 1912, figure 42 127 shows, at that time the navigable Cut still did not continue to the river, also illustrating the remnants of the railway lines and the blocked Cut. Figure 40 also shows that the dam across the Cut at the Neath end was still closed in 1914, with “Dam to be removed” indicated at that point.

A GWR map of 1912, figure 42 127 shows, at that time the navigable Cut still did not continue to the river, also illustrating the remnants of the railway lines and the blocked Cut. Figure 40 also shows that the dam across the Cut at the Neath end was still closed in 1914, with “Dam to be removed” indicated at that point.

The Cut appears to have retained this upper dam structure for some time, still appearing on OS maps into the 1940s, although an aerial view, figure 43 126, circa.1948 shows the dam to be at least partially breached by that time.

Figure 42 GWR map of 1912, still showing the outline of railway lines built for the earlier Neath Floating Dock, with the Cut remaining dammed from entering the river on the Neath side

Figure 43 Showing the Neath end of the navigable Cut (top of picture), which appears to have been partially breached by 1948

Figure 44(a) 128, gives a view of the same area in the early 2000s, with a nearby rail remnant shown in figure 44(b) 128. The rail is probably placed there simply to cross a later breached area, no tramway or railway having been planned along that embankment.

Portions of the Cut on the Neath-side of the swing-bridge railway line remain visible, figures 2(b), 45 128. A small inlet still ebbs and flows through the breached Neath-side dam on high tide, the original banks of the Cut now lined by vegetation. This inlet flow is curtailed at the original draw-bridge area.

Portions of the Cut on the Neath-side of the swing-bridge railway line remain visible, figures 2(b), 45 128. A small inlet still ebbs and flows through the breached Neath-side dam on high tide, the original banks of the Cut now lined by vegetation. This inlet flow is curtailed at the original draw-bridge area.

Figure 45 View along the small inlet Neath-side of Cut, lined by vegetation.

Figure 45 View along the small inlet Neath-side of Cut, lined by vegetation.

Over many years, the domestic refuse tip on the Briton Ferry side had been engulfing the marshland, gradually encroaching towards the Cut which has now almost been totally enveloped on that side of the railway, figures 2(b), 46 3. In recent times it has been landscaped although the Cut outline remains; no doubt this expansion will continue until the river is reached along its length in that area.

Figure 46 Aerial view showing filled-in Cut to the right on the Briton Ferry-side, with remnants of the lock on the west-side of river

Figure 46 Aerial view showing filled-in Cut to the right on the Briton Ferry-side, with remnants of the lock on the west-side of river

At the south end, the planned diversion of the Cwrt Sart Pill was not realised and it maintains its original course into the river.

6.3 Navigable Cut Bridge

As mentioned, section 5.0, the original retractable span may have been replaced circa. 1911. The piers of the original draw-bridge are shown on 1964 OS maps 129 but not in the 1968 130 version. It may be assumed therefore, that the bridge over the navigable Cut and associated piers were replaced at some point post-1965. Figure 47(a) 64 shows the piers in 1946 but they have been replaced by 1976, figure 47(b) 131. The simpler structure built over the by-then silted-up Cut, effectively dammed the Cut, although a small opening exists for water passage at extreme high tides. The change in water passage through the Cut can also be clearly seen, changing from a wide flow throughout in 1946 but in 1976 flowing up to the new bridge, with only a trickle on the Neath side from tidal inlet at that side as mentioned, section 6.2. Some possible remnants of the original draw-bridge abutments are still to be found, although largely hidden by dense undergrowth 128, figures 47(c), (d).

Figure 47 Navigable Cut bridge (a) 1946 showing piers (b) 1976 showing modified bridge and effect on Cut water passage (c) Possible remnants of original Cut draw-bridge abutments hidden among vegetation (d) View along railway embankment.

Figure 47 Navigable Cut bridge (a) 1946 showing piers (b) 1976 showing modified bridge and effect on Cut water passage (c) Possible remnants of original Cut draw-bridge abutments hidden among vegetation (d) View along railway embankment.

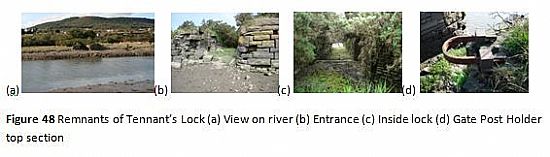

6.4 Tennant Canal Lock and Graving Dock

Evidence of the Tennant canal lock is still to be seen, running up from the edge of the river, figure 48 128.

The post holder, figure 48(d), is probably a similar style to that which would have held the gates to the main harbour lock. Unfortunately, the graving dock which remained on OS maps up to the 1960s, has since disappeared under the A465 dual carriageway.

6.5 Lock and Basin

The west lock gate cross-walls and abutments, with their adjoining entrance lock basin wall largely remain, figures 46, 49 128, although the seaward side has deteriorated more quickly than the float-side.

Figure 49 View of west lock lower and upper chamber entrance cross-walls and adjoining entrance lock basin wall.

The height of wall remaining is approximately 10-15 feet extending down to with about the same depth below the mud. An attempt has been made to align and show the relationship between the more complete remaining structure of the west lock upper entrance chamber and the original plan, figure 50.

Figure 50 Collage of west lock upper entrance chamber, from top to bottom: slightly skewed front view, original plan, plan view of remaining area

Further details of the west lock upper entrance chamber area, figure 51 128, illustrate the intricacy of the entrance chamber design.

Figure 51 Remaining sections of the west lock upper entrance chamber gate area (a) Lock gate heelpost area with intricate hollow quoin curved masonry and slightly curved area (wall recess) to receive gate on opening (b) Adjacent section also showing gate recess and inner masonry(c) Top view of hollow quoin lock gate heelpost and wall recess area (d) Top view hollow quoin for gate heelpost (e) Close-up of inner section of east upper chamber entrance.

The west upper lock entrance chamber section is largely intact, figures 49-51 and would have been capped with coping, being curved on the water-side. Figure 51(b) shows the section of wall where the outer masonry layer no longer remains thereby exposing the masonry in-fill behind. Figures 51(a),(d) clearly show the intricacy and accuracy of the lock gate heelpost quoins. The slot on top of the heelpost quoin, figure 51(d), may be a location for a cramp, i.e. a large staple-shaped section that would be fitted to prevent movement of vulnerable sections such as at the heelposts, although there is no groove to accommodate the flat section. Therefore, it may be for a locating-pin during dressing. The heelpost would be fitted such that there would be minimal leakage between post and adjacent masonry when the lock is filled, sealing under pressure, although masonry would still requiring accurate dressing. Figures 50, 51(a,b) illustrate the recess into which the opened lock gate could locate to ensure the maximum width of the lock was available on opening. Figure 51(e) clearly shows the vertical recess/slot (darker line) on the inner-side of the basin at the rear of the hollow quoins. This runs the full height of the abutment and may be that formed for the location of the wrought iron girders used across the entrance as part of the temporary dam.

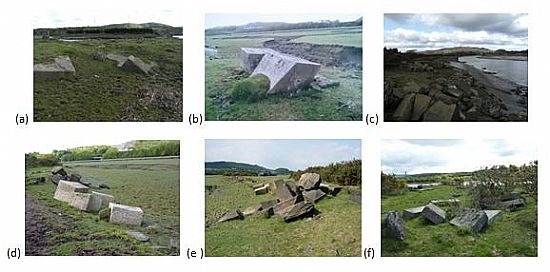

Some of the construction removed during removal of the lock in 1908, was placed on the marshland alongside the west of the lock and remains to this day, figure 52 128.

Figure 52 Remants of lock placed waterside on marsh during the lock removal of 1908 (a) Gate heelpost quoins (b) Intricate shaped wall block (c-f) Various other complete and damaged sections

Some of the very substantial, intricately carved angular blocks shown in figure 52, may have been part of the entrance lock basin or lock wall. The main, sharply angled block shown in figure 52(b), also has a slot similar to figure 51(d), again with no groove, so the slot may again be used as a location when dressing stone requiring increased level of accuracy than standard.

REFERENCES FOR PART SEVEN

126. National Museum of Wales

127. Neath Reference Library

128. Hywel Rogers Personal Collection

129. OS 1964, National Library of Scotland

130. OS 1968, National Library of Scotland

131. cambridgeairphotos.com

END OF PART SEVEN

PART EIGHT

7.0 Considerations Regarding the Failure of the Neath Floating Dock Scheme

While researching this article, no single incident or outcome has been identified as the cause of the failure by NHC to complete the Floating Dock scheme, at least not based on the remaining extensive contemporary records. However, a number of elements which, when combined, led to the vicious circle of expense, were: financial management, the accident of 1884, and time management. Each of these has been considered separately below.

7.1. Financial Management

From the outset, NHC quite rightly sought to minimise cash outgoings by seeking all those involved in the project, from Engineers to suppliers, to accept bonds in payment wherever they could. NHC appear to have been very thorough in their monitoring and control of the technical parts of the project although the management of finances and contracts, despite detailed accounting, raise questions.

Whilst some costs were obviously necessary, Parliamentary and previous contractors’ costs up to 1885 comprised about 7% of the £370,000 available, with interest about 17% of this total, as given in the list of ‘Old Liabilities’, figure 24(b), from the New Works 1885 balance sheet. While the interest seems excessive there would of course have been the risk that a lower rate would not have attracted investors in the first place, albeit an acknowledged difficult balance.

Examples of possible unnecessary costs, figure 24, are those for associated debenture costs totalling approximately £19,000 (*£2,497,000) and ‘Law and Parliamentary Expenses’ totalling £8,235-12-2d (*£1,083,000). If initial costings had been more definitive, then renewed funding costs and expense of additional Acts would not continue to have been required, reducing outgoings. The settling of claims against the initial three contractors would also prove to be very costly at more than £17,200 (*£2,143,000), ostensibly due to the inability of NHC to obtain the necessary land and obtain finance prior to entering into binding contracts. Also, perhaps not all of the ‘Law’ expenses should have been against the ‘New Works’ account, such as Bill opposition.

7.2 The Accident of 19th August, 1884

It appears that even ahead of excavation for the foundations at the lower lock entrance, there were issues with piling. As later reported by Wilson, these were compensated-for accordingly with extra work, by increasing both the depth of piling and increasing the amount by placing two rows instead of one. However, the reasoning behind these changes to planned work and under whose instruction or with whose agreement is unclear. Daniel and/or Barbenson must have given the go-ahead for this extra work which, with the attendant extra costs, would surely have been brought to the attention of Wilson and/or NHC who, in turn, should have investigated further. Potentially, the different soil content may have been identified and addressed satisfactorily at that stage. It is strange that there is no record of the additional work being mentioned by Barbenson, Daniel or Wilson, or any record of this extra work on the monthly certificates.

Prior to any excavation, apart from borings, the true nature of the soil would not have been known. It is also reasonable to expect that during any excavation, the on-site Resident Engineer, Barbenson, would consider the type of soil extracted to ensure it matched the boring results. These were part of the plans that Wilson held, so it must be assumed that Barbenson was also working to the same plans. As such, any difference between the soil expected and actually found would be identified and acted-upon. Why was the excavated soil not reported as being different to the borings? Brereton later reported that on excavation, soil conditions encountered had indeed differed from that reported in the earlier borings and plans should have been modified accordingly. Nevertheless, immediately after the accident, Wilson reported that he had been ensuring he followed the plans exactly as provided by NHC, even though he stated he disagreed with both the thickness and driven depth of piles being used, albeit in relation to when being driven into sand, which of course differed to the borings. He expected that Brereton would have considered the correct requirements of piling in combination with the soil type from the boring results and he was simply carrying-out the plans he was given.

It is unclear if the subsequent comments by Wilson regarding piling factors when driving into sand were simply his thoughts, or, based on hindsight as he now knew that sand-only was found during excavation, or if he was aware of the sand problem from the start and issued or agreed with the instruction to strengthen the nature of piling. Even then, the modifications could not meet the subsequent requirements as he deemed necessary. While it would be expected that, Barbenson at least, and Daniel along with Wilson, if informed, should be aware of the subsequent soil irregularities and the potential need for remedial action, there is no record to confirm who know what and when. It is likely that either Barbenson, or Barbenson and Daniel, knew and believed the extra work already in place (due to Wilson) was sufficient, or Barbenson, in the first instance did nothing, either by ignorance or choice and hence the difference remained unacknowledged until too late. There also remain the results of the additional borings about a year prior to the accident where no clay was found up to 14 feet below the river bed, albeit not at the location of the lock. Were these findings potentially damaging but ignored? NHC quite rightly sought to apportion blame for the accident to recover the associated costs, although not even the arbitrator was prepared to consider evidence and arrive at a decision. There certainly did not appear to be any disharmony or finger-pointing among the Engineers whatsoever. All the Civil Engineers involved in the scheme had a good background and no doubt knew each other well, a least based on the proximity of their business addresses and seemed to work well together. No doubt they had many private conversations regarding the project in London, away from NHC. This would not necessarily be deleterious but their close relationships may not have been to the advantage of NHC. When finances became depleted NHC quickly turned on both Daniel and Wilson, although Brereton continued to enjoy a good working relationship as he had done for many previous years and would continue to do so up to his demise.

Following the accident, by NHC having two independent reviews it is difficult to know what they expected as a preferred outcome. At best it would be agreement with their consultant, Brereton, on the original proposals made with Wilson, any other option likely to incur extra cost. Whatever the final decision, the time taken to decide would have consequences on the deteriorating state of the existing works. It may have been better to implement the original remedial actions in full by seeking immediate finance, instead of ultimately chasing endless shadows.

7.3 Time Management

One of the main issues continuing as a common thread throughout this scheme is the somewhat inordinate amount of time taken between key stages of the project. As the years passed, the original plans became increasingly out-of-date. While it was no doubt difficult in the first instance to obtain the necessary finances to embark on this work, even when in-place and a contract signed, the lands issue had not been resolved. This first contract, signed three years after 1874 necessitated the land to have been obtained. The previous tacit land agreements did not result in satisfactory land transfer until about five years after the 1874 Act. A done deal is not done until it is done. The resultant delay was a major factor in losing the first contractor. By the time alternative finance schemes had been considered and failed, losing the next two contractors, work only began some eight years after the 1874 Act was given assent.