NEWS & MEMBERS ARTICLES

03 February 2026Welsh Women's Peace Petition

The 1923/1924 Welsh Women’s Peace Petition in Neath

A local study of the petition’s significance in the town

BLEDDYN SMITH

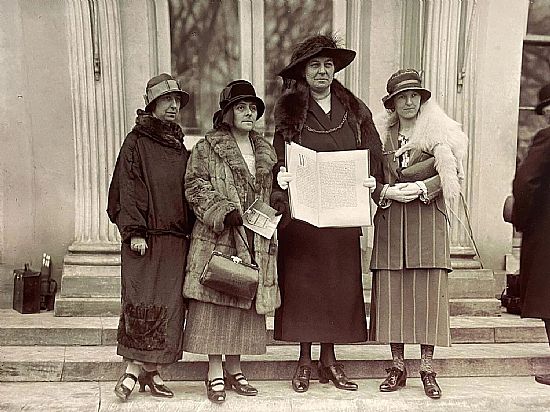

Gladys Thomas, Mary Ellis, Annie Hughes Griffiths and Elined Prys with the appeal in Washington D.C.February 1924 - National Library of Wales website.

Gladys Thomas, Mary Ellis, Annie Hughes Griffiths and Elined Prys with the appeal in Washington D.C.February 1924 - National Library of Wales website.

This article will discuss the Welsh Women’s Peace Petition of 1923 to 1924 and the stories of those who helped to organise the distribution of the petition in Neath and some who signed the petition.

The Welsh Women’s Peace Petition was organised by the Welsh branch of the League of Nations. The appeal was sent to the USA, addressed from the women of Wales to the women of America. It was created to promote global peace and a warless world in the wake of the First World War, as a memorial to those that were lost in the war. It was hoped that encouraging America to join the League of Nations would achieve this. The petition was signed by 390,296 women throughout Wales as well as in Welsh communities in London, Manchester, Liverpool and Birmingham. The idea was proposed at a Conference of the Welsh League of Nations in May 1923, with two main organisers: - Mary Ellen Pritchard for North Wales and Ceredigion and Ethel Elizabeth Poole for South Wales and Monmouth. The three key women involved in this, were Elined Prys, Mary Ellis and Annie Hughes Griffiths [President of the women’s committee of the Welsh League of Nations], who with Gladys Thomas, as part of a ‘peace delegation’ tour of the USA from February to March 1924[1], delivered the petition and appeal to the USA, including to the White House.

![]() The Signature of Mrs Naomi Thomas of 75 Lewis Road - NLW Ref. 25/59/2

The Signature of Mrs Naomi Thomas of 75 Lewis Road - NLW Ref. 25/59/2

Most towns and villages in Wales had their own committees for the local organisation of the petition, with a secretary or organiser appointed for each committee, with around 400 of them in total and Neath was no different.[2] The secretary for Neath was Mrs Naomi Thomas of 75 Lewis Road, the wife of George Ernest Thomas, a presbyterian minister.[3] Mrs Thomas was a native of Fishguard and had frequently moved around, due to her husband’s occupation. Mrs Thomas was new to the town, having moved into No.75 the year prior and although her residence in Neath was short, she had a significant impact through her role as Neath’s secretary for the petition. The treasurer for the petition was Miss Mabel Kenway of Highfield, Cimla.[4] Miss Kenway was from a notable Neath family, a keen social worker in the town, had worked as a nurse in her younger years and had nursed an elderly Florence Nightingale in London.[5] Miss Kenway was also the canvasser for the Cimla area, where she gathered over a hundred signatures and signed the petition herself, as well as her 84 year old mother, Sarah Harriet Kenway. The president of the Neath Committee for the petition was Mrs. TT Davies, whose husband was a member of the Welsh National Liberal Association and was an electoral agent to Thomas Elias who stood as Liberal MP for Neath in the 1923 General Election. [6]

Mabel Kenway, daughter of Llewellyn Brock Kenway and Sarah Harriet, his wife and granddaughter of James Kenway and Elizabeth, his wife, c.1900.

Mabel Kenway, daughter of Llewellyn Brock Kenway and Sarah Harriet, his wife and granddaughter of James Kenway and Elizabeth, his wife, c.1900.

NAS Z 52/2

Canvassers knocked on doors, explaining the purpose of the petition, inviting the female residents over 18 years of age from each home or establishment to sign. Women were asked to sign their name and address and each petition contained a description of the appeal, printed in both English and Welsh editions, as well as the instructions. Eventually, around 4,300 signatures were gathered from Neath, with signatures from almost virtually every street and road in the town, by women from all social classes and ages. It is groundbreaking to think of the sheer amount of effort that it took, particularly because many signatures were collected during cold, late autumn and winter months of 1923. Not all signatures were collected via door-to-door canvassing; for example, there are many signatures from businesses down The Parade, Windsor Road, Briton Ferry Road and Queen Street, with an array of addresses from shop and hotel staff, publicans and shoppers.

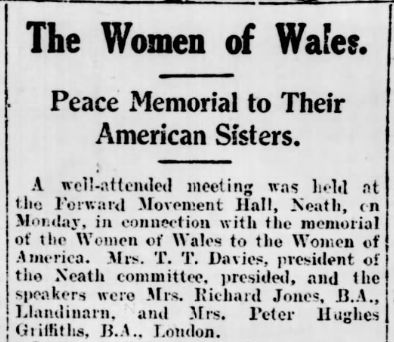

Now that the wheels had been set in motion by the organisers, meetings were held across Wales at churches, chapels and local institutions where speakers from the committee presented the mission of the appeal and petition. On the 5th November a meeting was held at the Forward Movement Mission and the speakers were Mrs Richard Jones, BA of Llandinam and Annie Hughes Griffiths, who stated to the residents of Neath that ‘This movement would be one of the wonders of the century.’[7]

South Wales Daily Post - 6th November 1923, p.6

PROMINENT INDIVIDUALS

Winifred Coombe Tennant (1874-1956) in 1922

Winifred Coombe Tennant (1874-1956) in 1922

Welsh Centre for International Affairs website

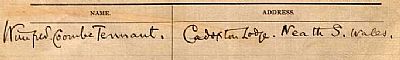

One very prominent individual that signed the petition was Winifred Coombe Tennant of Cadoxton Lodge. Mrs Coombe Tennant played an influential role in both politics and pacifism, being the first British woman to be a representative at the League of Nations in 1922.[8] Born in Gloucestershire, Mrs Coombe Tennant moved frequently but made Neath her home in 1895 when she married Charles Coombe Tennant of Cadoxton Lodge. Mrs Coombe Tennant had a shared experience with many women in the town, having lost her son, Christopher in the battle of Ypres in 1917. Mrs Coombe Tennant was a staunch Liberal politician, magistrate and suffragist and was also very passionate about Welsh culture and arts, known by her bardic name ‘Mam o Nedd’ and although she left the town in 1931, retained a deep connection with Wales.[9] She stated in her diary from May 1923 that she attended a Welsh League of Nations meeting where there was a women’s meeting about organising the memorial to the women of America.[10] Mrs Coombe Tennant stated that she was ‘Thankful to be able to work for peace in this war-ridden world.’[11] Mrs Coombe Tennant attended key League of Nations meetings about the appeal and correspondence between Mrs Coombe Tennant and Gwilym Davies, director of the Welsh League of Nations from September 1923, shows Davies asking her for some advice on how to spread more awareness about the petition requesting her to put something about the appeal in her local newspaper.[12]

Signature of Winifred Coombe Tennant

Signature of Winifred Coombe Tennant

Ref: Petition 21/96 - Blaenhonddan- NLW

Other prominent signatories include the following women. At Edgehill, Penywern Road, Caroline Elizabeth and Margaret Winifred Gibbins , two sisters and members of the well-known industrialist Gibbins family, both signed the petition as well as their servants. Annie Kate Gardner, wife of the councillor and tinplate manufacturer, Clement Sankey Best Gardner of Rookwood, Cimla Road also signed the petition. Additionally, Eleanor Jane Rees, mayoress of Neath for 1923, wife of Mayor and Alderman Joseph Cook Rees and their daughter, Sibyl Kathleen Rees of Glanffrwd, Cadoxton Road also signed their support for the cause.

THE WOMEN AND GIRLS OF ‘THE GREEN’

Thousands of ordinary working-class women

The overwhelming majority of women who signed the petition would have had some link to the losses inflicted by war, be it the loss of a husband, son, grandson, brother, nephew or neighbour. This petition gave women a chance to have a voice in a society that undervalued their opinions and autonomy. Until the Act of 1928, women still did not have equal voting rights to men, with the voting age being 21 for men and 30 for women. This petition was probably the only opportunity that many women had to sign their names, besides their marriage certificate. Those who could not write, signed an ‘X’ next to their names, signifying their approval despite the barriers that surrounded them.

Around a third of signatures from the community of The Green in Neath were signed with an ‘X’, reflecting the poor conditions and the lack of opportunities for literacy for working-class women in socially deprived communities. This was particularly so for middle-aged women, without educational opportunities in their youth. This reflects the social breadth of the petition, but also disparities of wealth. The Green was a poor and industrial quarter of the town, with residents living in harsh living conditions, in ‘court’ style housing, with many houses later demolished under the Slum Clearance Acts. Nevertheless, there was a strong sense of community feeling and the women of The Green banded together to campaign for peace from their doorsteps.

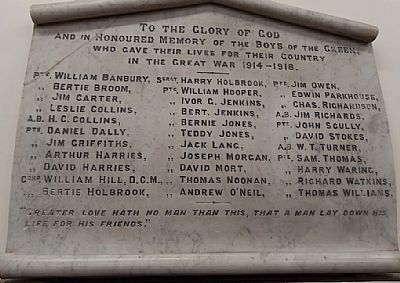

War Memorial at The Green Mission - unveiled in 1923

Two signatories from The Green were relatives of mine. My great-great grandmother, 55-year-old Jennie Phillips and her eighteen-year-old daughter, Jennie (my great-great aunt) of 18 The Green. Three of Jennie’s sons, named Bertie, Charlie and Tom Broom all served in the war, and Bertie was tragically killed. Bertie was a member of the Welch Regiment and was only 26 years old when he died in Gallipoli in 1915. Jennie was a mother to eleven children and was a former publican who by then was running a haulage contract firm and balancing a large, extended family. Jennie was a mother and a smart businesswoman, an extremely kind and charitable person, but also a force to be reckoned with! Jennie was just one of around 140 women and girls from The Green who signed the petition, all with their own personal reasons and circumstances for doing so and hers is just one story out of thousands of women across Wales.

My Great-Great Grandmother Jennie Phillips of 18 The Green, Neath (1868-1951) c.1902

![]() Jennie Phillips’ signature on the petition - NLW - Ref: Neath, 23/22/3

Jennie Phillips’ signature on the petition - NLW - Ref: Neath, 23/22/3

The war memorial in the Green Mission Chapel lists 33 men from The Green who were lost in the First World War and most of the men can be linked to a woman who signed the petition. These included 42 year old, Mary Griffiths of Lakes Court, a mother of five, whose husband, Jim Griffiths was killed, 37 year old Mary Hannah Bailey of Cornish Court, the widow of Jim Carter and 28 year old Maria Thomas of Lakes Court, the widow of Edwin Parkhouse. Many people from The Green came from large families, but most houses lacked appropriate space with some having as few as two to three rooms, housing multiple people. The loss of a husband or father would have further exacerbated the financial struggles that many families experienced during the turbulent twenties.

Other residents, such as Annie Noonan, of 25 The Green, Margaret Mort, of 27 The Green , Alice Collins of Cornish Court and Mary Ellen Parker of Harris Buildings, all lost sons in the war, just as my great-great grandmother had. Women from other families in The Green signed the petition, such as the Broom, Downman, Hill, Hooper, Moran, Noot, O’Connor, Spreadborough, Watkins and Webber families. Analyses of the names suggest that the majority of the women were housewives, wives of colliers, brick makers and tin workers. However, a few were younger women who worked in the brickworks, tinplate works or domestic service. Others ran public houses or lodging houses, but the majority of the residents were of similar social standing.

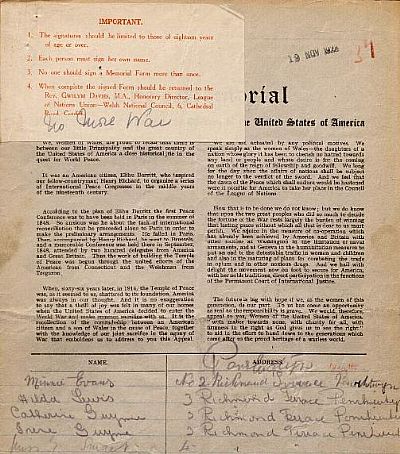

Similar losses were felt across other working-class districts of the town and this allowed ordinary women to proudly declare support for peace after experiencing firsthand the consequences of war. This was particularly poignant in parts of the Melyn and Penrhiwtyn, where local canvassers wrote, ‘No More War’ on the manifests for Evans Road, Walters Road, School Road, Morgans Road, Furnace Terrace, Richmond Terrace and Maesgwyn Terrace, echoing the devastation felt by the residents of those communities.

‘No More War’ petition for Richmond and Maesgwyn Terrace, Penrhiwtyn – 19th November 1923

Ref: Neath 25/116/1, NLW

The petition additionally offers a glimpse of social history into communities that have been lost to history. Many streets feature in the petition that either no longer exist or were demolished during the last century, such as Cattle Street, Duck Street, Glamorgan Street, The Latt, Russell Street and Zoar Row. Therefore, this is not only a very important form of women’s history, but it shows how much Neath has evolved and developed as a town in the past century. Therefore, the petition helps to freeze these communities in time allowing us an insight into lives of those who were born, married and died in these communities as ordinary people. Although both the houses and their residents are long gone, this petition is a testament to the existence of those communities and how they banded together in the aftermath of war.

ANOTHER WORLD

The Women and Girls of Victoria Gardens

A short walk by the canvassers through the Dark Arch, along The Ropewalk and London Road, to the area of Victoria Gardens would have quickly painted a different picture of the town, from the hustle and bustle of the busy shops, cafes and pubs of The Parade and Windsor Road. Signatories from Victoria Gardens and Rugby Avenue manifest included schoolteachers, clerks and wives of prominent businessmen or civil servants, with some homes having their own servants. This was certainly a very different life experience compared to the women and girls from what were designated ‘slum’ areas. Residents included Florence Davies who was head teacher of the Gnoll School and schoolteachers named Eileen Eggleton and Beatrice Yeo, who were well-educated, middle class women from well to do families, as well as Mary Joshua and Margaret Rees, wives of the ministers Seth Joshua and Rev T Maerdy Rees. Although the nineteen twenties presented new opportunities for a new generation of women, the gaps in wealth are clear through analyses of the occupations and homes of thousands of women who signed the petition. Despite disparities in personal circumstances and wealth, losses were felt throughout the social spectrum, such as by Miss Elsie Noot and Mrs Annie Noot of Victoria Gardens, whose brother and son was killed in the War.

![]() The signature of Mary Jane Joshua, The Manse, Victoria Gardens

The signature of Mary Jane Joshua, The Manse, Victoria Gardens

NLW - Ref: Neath 25/76/1

AN INSIGHT INTO A MULTICULTURAL HISTORY

Although they were divided by wealth and social status, all the women who signed this petition shared a connection, through voicing their desires for a warless world, no matter their social, religious or ethnic background. The petition reflects a rich cultural history in the town. There are signatures from some Irish women and their families who settled here, as well as those from mainland Europe, such as Paulina Zaremski of The Parade, a Lithuanian woman named Golda Leitz of Windsor Road, Phoebe Supper of Windsor Road (originally from Poland), Yetta King of Lewis Road (originally from Latvia) and Mrs Olga Gunter of Brookdale Street (originally from Norway). Golda Leitz’ son, Hyman served in the War, and was killed in 1917, aged just 23 years old. The Zaremskis, Leitz’, Suppers and Kings were Jewish families, which also reflects how the petition reached beyond a set religious denomination or belief. Other surnames reflect this diverse history, such as the Charliers, Rombachs and DuPonts and also the Diaz family from Briton Ferry. These were Welsh or English women, who married into Belgian, German, Swiss and Spanish families and such research uncovers hidden histories of mixed heritage families.

THE OLDEST AND YOUNGEST SIGNATORIES

Mrs Ann Porter of 2 Gnoll Avenue, potentially the oldest signatory of the petition from Neath.

South Wales Evening Post, 23rd December 1931

Although a good number of young, single women signed the petition, a high number were also housewives, mostly in a 20 to 60 age range. It seems that the oldest signature in the town was from Ann Porter, aged 91 years old, of Gnoll Avenue, who died in 1934, at the grand age of 102. Mrs Porter was the widow of a minister, having called Neath her home for many years, and saw the town vastly develop.[13] Other very elderly signatories included Ann Morgan of Llantwit Road and Maria Turner Toms of Maria Street; both impressively aged 88 years old, respectively.

On the other hand, there were young women who were just starting out in life, part of a new generation that would live through extensive changes in the twentieth century. They would experience the troubles of the Second World War after already growing up during the turbulent era of the First World War. There could definitely be younger signatories found on the petition in Neath, but so far, one of the youngest people seems to be 14 year old Meinwen Jones, of Bowen Street, even though the rule was that those who signed the petition had to be over 18 years of age. Despite their vast differences in age, young girls like Meinwen Jones and elderly women like Ann Porter, were united in a common cause for world peace and an end to war.

Rules for signing the peace petition was attached to every manifest

Rules for signing the peace petition was attached to every manifest

REPEAT SIGNATORIES AND EVIDENCE OF MALE SIGNATORIES?

Unfortunately, we will likely never know the names of most local canvassers, but the canvasser for Arthur Street, Geoffrey Street and Greenway Road, was Mrs Gwladys Moore, of Arthur Street. Mrs Moore listed each address in Greenway Road, striking it out if there was no one from that particular house present or willing to sign. For 22 Greenway Road, Moore noted ‘No Woman at 22 Greenway Road’. A search of electoral rolls, show an 86 year old retired constable named Christopher Seldon living at the address, it would be interesting to know the conversation that Mrs Moore and that man had. Nevertheless, the petition was interestingly signed by some men, which depended on the decision of the canvasser, as some canvassers later struck out male signatures. Some examples include George Richards of Union Road, Penydre who served in the First World War, Henry Smith of Gnoll Lodge, Walter Ivor Havard of Walters Road and William Thomas and his sons, Trevor and Rowland of Leonard Street. It is interesting that a small group of around fifteen men signed the petition, perhaps moved by personal experience of the War itself or the loss of sons, brothers or workmates and were able to bypass the instructions set out by the canvasser.

![]() ‘No Woman at 22 Greenway Road Neath’ – ref: Neath 30/156/4 NLW

‘No Woman at 22 Greenway Road Neath’ – ref: Neath 30/156/4 NLW

Interestingly, another clear rule was not to sign the petition more than once, but Doris Howarth, Iris Vaughan and Lilian Mort of Hillside, Lily Jones of Lewis Road and Rose Davies of Greenway Road, must have been very eager to sign the petition as they all signed it twice, appearing on more than one petition manifest. Iris from her home in Mary Street and presumably where she worked in Orchard Street, Lily at her home in Lewis Road and on the petition for Queen Street and Doris at the home of her in-laws in Eva Street and the family home in Lewis Road. Doris’ brother, Frederick Nicholas was killed in France in 1915 and both her parents had died by 1923, so perhaps this double entry was also to represent her beloved parents.

Other interesting and unusual features are some joint signatures by mothers and daughters. Edith and Violet Kelly of Greenway Road, Elizabeth and Flora Surman of Idwal Street and Annie Simmons and Hiral James of Ena Avenue jointly signed their names on the petition. This reflects mothers and daughters united in a joint effort to encourage world peace, or perhaps additionally to save space on the petition sheet.

![]()

Joint signatures - Mrs & Miss Surman of 15 Idwal Street

Ref: 30/155/3- NLW

In conclusion, this article has demonstrated the significance of the peace petition’s history. It has now been a century since this awe inspiring effort took place and we should never forget the efforts of not only the organisers, secretaries and treasures, but also the thousands of ordinary Welsh women who signed their names for the hope of a warless world for future generations. This is a special and unique history as it is a movement in history that involves our forebearers. It is a vital aspect of women’s history and using case studies from specific towns help to bring to life the woman who signed the petition and gives us a small glimpse into their lives in post war Britain. Did you have a female ancestor over the age of 18 living in Wales in 1923? Why not visit the website and see who you might discover?

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Primary Sources:

Photograph of my Great-Great Grandmother, Jennie Phillips, c.1902

Photograph of Mabel Kenway, daughter of Llewellyn Brock Kenway and Sarah Harriet, his wife, and granddaughter of James Kenway and Elizabeth, his wife, c.1900, Records relating to the Kenway family of Neath - Neath Antiquarian Society Archives - Ref: NAS Z 52/2

Cymru a Byd Heddwch and English translation Wales and World Peace, Winifred Coombe Tennant – WGAS - Ref: D/D T 4027

Gwilym Thomas of the League of Nations Union, Welsh Council to Winifred Coombe Tennant, concerning the memorial from the Women of Wales and Monmouthshire to the Women of America, 19th Mar. 1923 – 6th Nov. 1923, Tennant Estate Papers, WGAS - Ref: D/ D T 4081

South Wales Evening Post - 6th November 1923, p.6

South Wales Evening Post - 23rd December 1931, p.5

Neath Guardian - 3rd January 1947, p.6

Secondary Sources:

Between Two Worlds - the diary of Winifred Coombe Tennant 1909-1924 - Peter Lord (ed.) - (2011) - NLW

Yr Apêl/ The Appeal 1923-24, Hanes Rhyfeddol Deiseb Heddwch Menywod Cymru/ The Remarkable Story of the Welsh Women’s Peace Petition - Jenny Mathers and Mererid Hopwood (eds.) - (2023) Y Lolfa

Neath and Briton Ferry in the First World War - Jonathan Skidmore (2018) published by the author

Dictionary of Welsh Biography, entry for - Winifred Margaret Coombe Tennant, https://biography.wales/article/s2-COOM-MAR-1874, Date accessed: 18th November 2025

The Welsh Women’s Peace Petition - National Library of Wales - https://peacepetition.library.wales

[1]Aled Eirug, ‘The Aftermath of the Great War in Wales and the Search for a Lasting Peace’, in Jenny Mathers and Mererid Hopwood (eds.), Yr Apêl/ The Appeal 1923-24, Hanes Rhyfeddol Deiseb Heddwch Menywod Cymru/ The Remarkable Story of the Welsh Women’s Peace Petition, (Talybont, 2023), p.50

[2] Catrin Stevens, “Arm in Arm” for Peace: Organising the Appeal’ in Jenny Mathers and Mererid Hopwood (eds.), Yr Apêl/ The Appeal 1923-24, Hanes Rhyfeddol Deiseb Heddwch Menywod Cymru/ The Remarkable Story of the Welsh Women’s Peace Petition, (Talybont, 2023),p.81

[3] South Wales Daily Post - 6th November 1923, p.6

[4] South Wales Daily Post - 6th November 1923, p.6

[5] Neath Guardian - 3rd January 1947, p.6

[6] South Wales Daily Post - 6th November 1923, p.6

[7] South Wales Daily Post, 6th November 1923, p.6

[8]Aled Eirug, ‘The Aftermath of the Great War in Wales and the Search for a Lasting Peace’, in Jenny Mathers and Mererid Hopwood (eds.), Yr Apêl/ The Appeal 1923-24, Hanes Rhyfeddol Deiseb Heddwch Menywod Cymru/ The Remarkable Story of the Welsh Women’s Peace Petition, (Talybont, 2023), p.48

[9] Dictionary of Welsh Biography, entry for - Winifred Margaret Coombe Tennant, https://biography.wales/article/s2-COOM-MAR-1874, Date accessed: 18th November 2025

[10] Between Two Worlds - the diary of Winifred Coombe Tennant 1909-1924 - Peter Lord (ed.) – (2011) – NLW p.390

[11] Between Two Worlds - the diary of Winifred Coombe Tennant 1909-1924 - Peter Lord (ed.) – (2011) – NLW p.390

[12] Gwilym Thomas of the League of Nations Union, Welsh Council to Winifred Coombe Tennant, concerning the memorial from the Women of Wales and Monmouthshire to the Women of America, 19th Mar. 1923 – 6th Nov. 1923, Tennant Estate Papers, WGAS Ref: D/ D T 4081

[13] South Wales Evening Post - 23rd December 1931, p.5

05 January 2026Neath Aviators' Disaster

Flying Tragedy at Swansea Sands

In late September 1922 a road traffic accident occurred at Court Herbert, Neath when a young man aged 18 was injured after being crushed between a motor car and a wall. The young man suffered a leg injury. The driver of the vehicle promised the young man that he would make up any loss of earnings incurred due to the injury, but just a few days later on 3rd October the driver was killed in a flying accident in Swansea. The young injured man was my grandfather Eddie Soderstrom of St. Johns Terrace, Neath Abbey and the driver was Evan Henry Williams of ‘Hillsboro’ on Cimla Road.

This story is unusual due to the very low number of motor cars on the roads in 1922 and even more so in that it involves a flying accident when flying was still in its infancy. Two newspaper cuttings found in grandfather’s diary allow me to add details to the story that I heard as a child.

In 1952, under a regular column titled ‘It was 30 years ago today’ in the South Wales Evening Post, this short article was featured;

‘ Tuesday 3rd October 1922.

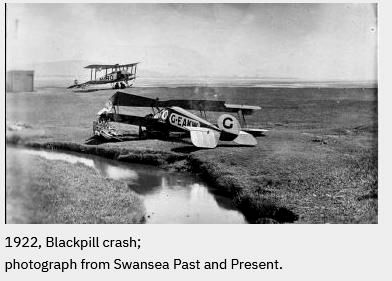

An Avro aeroplane crashed in the evening in shallow water off Swansea Sands near Brynmill, the rising tide rapidly covering the three inmates. The men who perished were Mr Evan Williams of Neath, a founder of Welsh Aviation Services who himself held a pilot’s licence; Mr Bush the pilot; and Sergeant Major Biggens RASC of the Drill Hall. Men who gallantly swam out to attempt a rescue were affected by petrol fumes from the burst tank. Later the wreckage was towed high and dry under the eyes of thousands of people. It was to have been Mr Williams’ last flight of the season.’

Evan Williams of ‘Hillsboro’, Cimla Road, Neath is described in the 1921 census as a turf accountant with his office at 11 The Parade. He was 42 years of age at the time of his death and a married man. In the 1911 census he is living in Resolven and describes himself as a financier and commission agent.

Evan Williams in 1916

He was not, in fact, a founder of the Welsh Aviation Company but had recently purchased four (ex RAF) AVRO 504K aircraft from the Welsh Aviation Company that had recently gone bankrupt. The four aircraft, three with 120hp Le Rhone engines and one with a 80hp Renault engine, were sold to him for £50, £40, £30 and £12.10s respectively. These single engine bi plane bombers had been produced in large numbers during World War 1, with 8,970 constructed. They became obsolete as frontline aircraft and were used extensively as trainers. Following the end of the war there were large numbers of surplus aircraft available for pilot training, pleasure trips, banner flying and even barnstorming exhibitions.

At this time, it became very popular to offer and experience joyrides in aeroplanes. These joyrides were available at various locations around the UK with a short trip costing 1 Guinea (approximately £100 today). The AVRO Transport Company flew joyrides in AVRO 504K aircraft from the beach at Brynmill, Swansea from July to October 1919 before it ceased trading in early 1920; although flights continued under licence. In December 1920 the Welsh Aviation Company was set up using 504K aircraft but folded in February 1922 after barely a year trading. At this point Evan Williams stepped in. Described as a financier and most likely a man with a keen eye for a business opportunity, he purchased the bankrupt stock of the Welsh Aviation Company.

Although Evan Williams claimed to have a pilot’s licence the pilot on this tragic occasion was Frederick Percival Bush (aged 33) of Norton Lane in Blackpill, where he lived with his wife Nellie. They had been married for three months. Fred Bush was born in Canning Town, London, however, his family settled in Neath with his father Alfred Bush being listed in the census as an India Rubber Merchant from Silvertown, London and his mother Mary McLachlan being from Australia. The family had lived at 81Gnoll Park Road, but were now at Fernbank, Neath.

Percy Bush enlisted on 11th Feb 1915 with the Royal Marines Divisional Train which was a horse drawn transport unit for the Royal Marines Divisional providing logistics support to the Royal Naval Division. He became a flight cadet on 1st April 1918 receiving his pilot training and finishing his military career with 44 Squadron in August 1919.

The third passenger was Sergeant Major John Stanley Hudson Biggins of the Royal Army Service Corps. He was a married man living at 27 Brunswick Street, Swansea.

The inquest into the accident recorded that death was due to asphyxiation through drowning for all three men. After being sent up for a trip, the machine was preparing to alight when it nose-dived into the bay.

SOURCES

South Wales Evening Post - 3rd October 1922

South Wales Evening Post - 2nd August 1919

Cambrian Daily Leader – 26th July 1915

Aircraft and accident details - asn.flightsafety.org

Photograph of accident - Swansea Past and Present.

Photograph of Evan Williams - afleetingpeace.org.

For another story about the Soderstrom family –

go to the top of this page and under News Index - navigate to

12th October 2017- SS.Main – The Sinking of a Skewen ship