Mariner’s Arms Footbridge, Melincrythan

PAUL RICHARDS

Background

The section of mainline railway that runs through Melincrythan at Penrhiewtyn passes under a fairly non-descript precast concrete footbridge near the entrance to the old Metal Box factory, which is officially known as the ‘Mariner’s Arms Footbridge’.

Mariners Arms Footbridge 2022 D Michael

Mariners Arms Footbridge 2022 D Michael

Bridge - Mariners Arms F/b aka Metal Box F/b - Footbridge - Pre-cast Concrete1

Mariners Arms Crossing Footbridge (NWR Bridge). - Engineering options being considered for this structure.2

The footbridge itself is over 100 years old and although there is currently no premises with the ‘Mariner’s’ name in the vicinity, the origin of the title goes back nearly 200 years. This article chronicles the history associated with the area close to the footbridge and the nearby location of the original public house named the ‘Mariner’s Arms’ - although reporters of the time could never quite agree if or where an apostrophe should be placed. Clearly the pub was not for the sole use of one mariner!

Origins

An Act of Parliament3 was passed in May 1798 permitting a 2 ½ mile extension to the Neath canal from near the Melincrythan Pill to Giant’s Grave; the enterprise was duly completed on 29th July 1799. These works incorporated a dock at the area virtually opposite the later road junction of Herbert Road and the Main Road (originally named New Turnpike Road). This latter road was built during 1816-1818; the plan below shows both the dock and road circa 1824.

Plan of area around canal dock near Penrhiewtyn circa 18244

With both a dock and nearby main road thoroughfare it would, no doubt, seem good business to build a public-house in that area. Although the precise date of the subsequent building of these premises, named the ‘Mariner’s Arms’ remains unknown, to-date the earliest found reference is that of 1830 in relation to a proposed railway line between Aberpergwm and Briton Ferry, where it is simply shown as a landmark along the length of the line.5

Mariners Arms landmark - map of proposed railway line from Aberpergwm to Briton Ferry, 1830.

The UK census of 1841 showed Thomas Deane (Publican) as residing at the ‘Mariners Arms’ along with his wife and two children and two other families living in the same building.6

It would seem, therefore, the premises were not just a public-house but also provided accommodation. Pigot’s Directory of 1844 shows Thomas Deane as the publican but by late April 1845 the landlord was Henry Bevan.7 The same year two men were charged with his assault ‘…landlord of the Mariners’ Arms, Briton Ferry’, the case being withdrawn on defendants Thomas Evans and Phillip Hill paying costs.8 A tithe map drawn up in 1846 is the first depiction of premises at the head of the dock on land owned by Herbert Evans and occupied by William Mockford.9

Tithe Map 1846 showing premises at head of dock

There is no detailed information of the premises; the surrounding land being merely described as part of marsh’ and used for pasture. It has to be assumed, therefore, that this structure at the dock was the Mariner’s Arms public-house.

July 1848 saw the publication of details relating to an assault by ’ Isaac Griffiths, of the parish of Lantwit-juxta-Neath, haulier…’ on Ann Tamplin, wife of Thomas Tamplin, the married couple residing at the Mariners’ Arms. The defendant was stated as having been drinking in the complainant’s house and subsequently ‘…proceeded to take improper liberties with her’. The case was proven with a ‘…penalty of 40s, and costs, or to be imprisoned in the House of Correction at Swansea, for the term of 3 weeks.’ It is not known what option was taken.10 Significantly, with the building of the main-line railway section through Neath, in 1848, progress of the line was reported as being nearly complete between Baglan and Neath where ‘…at a place called the Mariners’ Arms, an important branch strikes to the west to Britton Ferry and Giant’s Grave coal wharves.’ 11 The arrival of the railway would have a dramatic effect on the future of this public-house.

On the 16th December that same year, the Mariners Arms was used to hold an inquest into the death of Thomas Treharne aged 24, a worker at the nearby Melyncryddan Chemical Works. Treharne had been walking on a plank across a boiler containing acidifiable lime when he slipped and fell in up to his waist. He subsequently died three days later leaving a widow and child.12

The South Wales Railway eventually opened the mainline through Neath circa 1850 resulting in the Mariner’s Arms being effectively stranded with the canal to one side and the newly built railway on the other. Although crossing the tracks from the main road for access to the Mariner’s Arms was permissible the safety of undertaking such an action would be questionable at the best of times without having to consider the potential state of inebriation of their customers. A Trade Directory for 1850 shows the ‘Mariners’ Arms, Melincrythan’ as being run at that time by John Joseph.13 In December of 1850 the license was reported as having been transferred to Mr. Henry Bevan (even though previously reported as landlord in 1845).14 Bevan was resident in the 1851 census, being recorded as a ‘widower’ living with his mother, son and a servant.15 At this time it seems that there was only one additional family in residence.

Census 1851: Henry Bevan, Brewer & Victualler, Mariner’s Arms plus second family

A somewhat bizarre incident generated national interest and was widely reported when in 1852 a hare had been found opposite the Mariner’s Arms with its two hind legs cut off apparently having been in contact with a South Wales Railway engine '….having evidently run over poor puss.'16 It must have been a quiet news day. No further entries have been found in any later trade directories in reference to this particular public house, although other premises bearing the same name existed in Castle Street, Neath over the next 10 years or so.17,18,19

A New Name

A significant event occurred in 1852 when the Mariner’s Arms and associated land was sold to The South Wales Railway Company (SWRC) for £1,100. This encompassed ‘Part of the Old Neath Canal Dock…an inn called the Mariners’ Arms…and…land, formerly part of Melincryddan Farm’.20 It is likely that soon after this sale the Mariner’s Arms ceased to exist as a public house. No doubt one of the reasons for the sale would have been the stranding of the business and it would be prudent therefore for the land etc. to be purchased by SWRC with it being unlikely the new owners would wish to be in control of a public house alongside a line which customers needed to cross to get access. Unfortunately, the 1861 census does not provide any clarity as to the use of the Mariner’s Arms at that time despite the enumerator’s route purportedly beginning at this very place.

A page from the 1861 census showing the start of the enumerator's route at the Mariner's Arms.

The nominal entries do not mention the building at all, neither do any other census returns in the Neath and nearby areas. It is possible that the building was uninhabited at the time and omitted from the returns although even then it should have been recorded as such. Later that decade it must be assumed that the (old) Mariner’s Arms was by now a substantially white painted residence as from this point forward it is variously referred to as the ' Old White House' or simply the 'White House'. The first reference to the new name came with Poor Rate collections of 1869 which noted ‘…from the White House at Melincrythan, to the union house…’.21 Now owned by SWRC it was likely to have been occupied thereafter by personnel associated with the railway, as indeed shown in the 1871 census

The 1871 Census shows the 'White House' occupied by David Thomas and his substantial family.

Whilst previously living elsewhere in 1861 the Thomas’ were now at the White House in 1871, David having been a railway clerk previously but was now a Station Superintendent. With such a large number of children there was probably no room for another family in the White House! Both the Mariner’s Arms and White House titles were used in the Parliamentary Bill of 1872 relating to the ill-fated Neath Floating Dock, ‘…at the house called the White House, formerly the Mariner’s Arms Public-house…’,22 An extract from an associated (undated) map shows the location of the ‘Mariners Arms’ onto which the intended railway lines of the floating dock were later added.23

Part of newspaper report on the Parliamentary Bill 1872 Bill and part of a map detailing dock-associated railways showing the location of the ‘Mariners Arms’

The premises are clearly shown situated between the canal and the main railway line. The original map is probably circa mid-1850s due to other features such as Briton Ferry Dock being included elsewhere. Also, while the Mariner’s Arms is shown on the map it should not have been named as such by about 1861 and certainly not in 1872. The map was probably not produced locally as evidenced by the strange spelling for locations including Mollygruthan and Penrwiting.

By 1877 the area around the White House had changed considerably, with both housing and industry being developed alongside the railway and main road.24

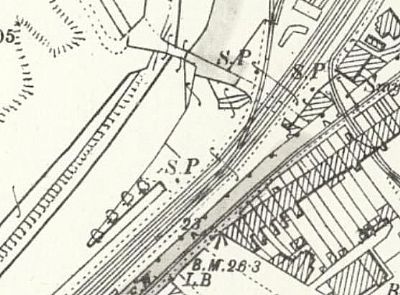

Ordnance Survey map1877 showing development around the canal dock area

At this time crossing the railway line for both pedestrians and transport simply involved traversing the rails at the crossing point to directly access the canal bridge.

In the census of 1881 there is no mention of any of the earlier names for the building and the Thomas family was now living in ‘Idris Villa’ next to ‘Pencaira Villa’. Initially it was considered the former could be yet another ‘new’ name of the White House, but it actually appeared amongst a series of villas in the Pencairau area which is somewhat removed from the original location of the White House. From the 1891 census it seems these villas were grouped together under the name ‘Pencaira Villas’, where the remaining Thomas family now resided. Nonetheless, when David Thomas died in 1897 it was reported that he died at his residence ‘Idris Villa’, yet another example of obsolete names remaining in use. The report of his death also included details of the accident that he befell about 20 years earlier whereby on crossing the railway line he was knocked down by an engine, the wheels running over a pocket knife that was in his coat pocket!25 In a fatal accident report of 1886 the railway crossing is referred to as 'Mariner’s Crossing, Melincrythan' where Daniel James, employed as a gateman at the crossing was run over by a train and 'frightfully mutilated'. It seems that David Thomas was indeed very lucky at the outcome of his own earlier accident.26

The census of 1891 shows no entry for premises resembling the Mariner’s Arms or White House in the area. It is assumed that they were no longer in use and had been demolished. However, references to the building/area continued. In 1891 the Great Western Railway (who had absorbed the SWR in 1863) stated that they would place a man at the 'White House crossing' between 6 am and 6 pm due to increased traffic.27 Again, the 'Old White House' was noted in relation to a suicide drowning in the area 28 and at an inquest in 1893, held to review the sudden death of a signalman, Peter Dargarville, it was stated that he expired in the signal box at the 'White House crossing' - it was concluded that he died of 'heart disease'.29 It is possible that the use of the term 'old' in this context meant that it no longer existed. However, the report into an attempted murder case of a 'deaf mute' who was potentially stabbed, robbed and thrown into the canal in 1896 stated '…he was seen without a hat crossing the bridge near what is known as the White House.' The outcome remained a mystery to the police at the time.30 By 1899 the premises is no longer featured on Ordnance Survey maps although the dock remained depicted.31

Ordnance Survey map 1899 with the canal dock still evident

Amazingly, yet another fatality occurred near the 'White-House crossing' in January 1900. The inquest heard that James Chappell aged 59, a plate layer and ganger of nearby Helens Road was knocked down by a 'special cattle train' and 'cut to pieces' after stepping into the path of the train for no apparent reason. A verdict of accidental death was returned.32 A further death followed in August 1901 when an engine stopped at the 'White House Crossing'. The fireman, WH Jenkins aged 23, of nearby Furnace Terrace disembarked the engine to check on a report of 'something wrong behind' and was immediately struck by a passing express train, he was '…struck on the head by the engine but the train did not pass over him.' A verdict of accidental death was once more returned.33

Based on the number of previous accidents it was not before time that by 1913 a footbridge had been built over the railway. This is almost certainly the same crossing that exists today i.e. the Mariner’s Arms Footbridge.34

Ordnance Survey Map 1913 with footbridge in place nearly adjoining the canal bridge

The railway crossing-point known as 'White House Crossing' and/or 'Mariner’s Crossing' had, therefore, been effectively replaced, at least for pedestrians, by the footbridge. This new bridge needed a name and would at some point become officially called Mariner’s Arms Footbridge. It would subsequently survive two World Wars and regularly carry significant foot-traffic not just for casual users but for the many thousands of workers in the nearby large industries that could be readily accessed via the footbridge such as the Japan Works, Eaglesbush Works and, of course, the later Metal Box.

Of these industries only the buildings of the Metal Box factory remain (albeit in name only) with the Mariner’s Arms Footbridge now crossed predominantly in pursuit of leisure activities giving users access to the extensive canal footpaths and for the more adventurous to the surrounding marshlands. Thus, the name of a long-gone substantial public-house which once rested at the head of an also long-gone canal dock remains in use to this day continuing as sole testament to the history of the area 100-200 years ago.

REFERENCES

1. Cardiff to Swansea Journey Time Improvement GRIP1 Intervention Study, Doc. Ref. 161034-NRD-G1-CDSW-REP-EMF-100000, Network Rail, 2018

2. Network Rail Electrification Work on London to Swansea Railway Main Line and its Effect on Neath Port Talbot Structures and Highway Network, Environment and Highways Cabinet Board, 23/7/2015

3. ’An Act for extending the Neath Canal Navigation, and for amending an Act, passed in the Thirty-first Year of the Reign of His present Majesty, for making the said Canal, 26th May 1798’

4. Map of Canal and Waterways, NAS RE 13/15

5. Plan of intended railroad Neath Valley to Briton Ferry, June 1830, SWMM 6/13/11 (WGAS)

6. UK Census Returns 1841-1891.

7. Pigot & Co.s Directory 1844

8. The Welshman - 25th April 1845

9. Tithe Maps (NLW)

10. Cardiff and Merthyr Guardian Glamorgan Monmouth and Brecon Gazette - 15th July 1848

11. Monmouthshire Merlin - 25th November 1848

12. The Principality - 22nd December 1848

13. Hunt & Co.’s Directory 1850

14. The Welshman - 13th December 1850

15. The Welshman - 12th December 1856

16. The Globe - 11th February 1852

17. The Welshman - 12th December 1856

18. Swansea and Glamorgan Herald - 6th March 1861

19. Swansea and Glamorgan Herald - 9th December 1860

20. Draft Conveyance 1852, NAS RE 8/60

21. The Cambrian Daily Leader - 30th January 1869

22. The Cambrian - 15th November 1872

23. Map circa mid-1850s, source unknown

24. Ordnance Survey Map - 1st Edition, 1877 (NAS)

25. South Wales Echo - 18th June 1897

26. South Wales Daily News - 9th November 1886

28. The Bridgend and Neath Chronicle - 9th October 1891

27 The Cambrian - 18th November 1892

29. The Cardiff Times - 16th September 1893

30. The Cardiff Times - 16th July 1898

31. Ordnance Survey Map - 1899 (NAS)

32. Evening Express - 6th January 1900

33. The Cambrian - 9th August 1901

34. Ordnance Survey Map 1913 (National Library of Scotland)