SMOG

MARTYN GRIFFITHS

The London 'pea-souper' fog of 1952 Getty Images - public domain

Older readers will remember the horror stories concerning the London Smog in the early 1950s that gave rise to the Clean Air Act of 1956. Younger ones will certainly remember the pictures of China’s smog laden cities prior to the Beijing Olympics and the concerns about the health of athletes taking part.

The word SMOG [a mixture of smoke, gases, and chemicals, especially in cities, that makes the atmosphere difficult to breathe and harmful for health] was not coined until the early years of the twentieth century, but its constituents – smoke and fog combined – had been around a very long time. Even in ancient Rome, Seneca complained about 'the stink, soot and heavy air.' In 1285 London's air was so polluted that Edward I established the world's first air pollution commission; and centuries later Shelley wrote: 'Hell must be much like London, a smoky and populous city.'

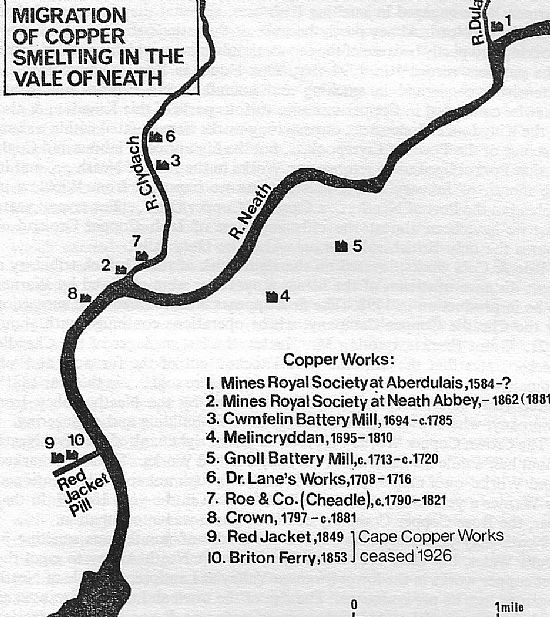

However, these are not just tales of distant parts. Neath had its own smog problems connected to the industrial revolution which had come early to the area. In the eighteenth century, for two-thirds of the year a cloud of smoke emanating from the many factories, would descend on the town. The autumn months were the worst when, during calmer periods, smoke particles, mixed with fog gave rise to a yellow-black cloud. The problems probably started when the first of the Mackworth's started his copper works in Melincryddan, at the start of the eighteenth century. Other factories produced smoke but copper smoke was the worst of all.

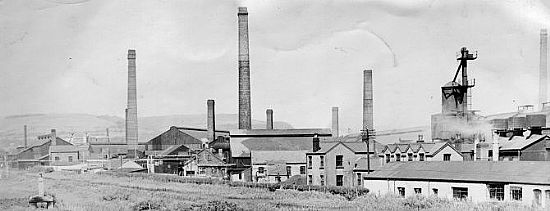

Chimneys at Melyncryddan NAS Image

Many of the tourists who came to the Neath valley to view the beauties of its waterfalls and its abbey were appalled by the marks of industry. Some of their remarks were included in the article on Traveller’s Tales last October. Their comments stretch over nearly a century:

1774 - Henry Penruddock Wyndham : 'the country here … is spoiled by the neighbourhood of copper works, lime kilns and coal works, which here abound, and the air is poisoned, and even darkened, by the continual smoak arising from them.'

1798 - Rev. Richard Warner speaking about Gnoll House: 'The great Manufactories standing at a distance of not more than a mile to the south-west of it, the general prevalence of the wind must wrap the House in highly disagreeable and perhaps pernicious, fumes, three-fourths of the year.'.

1824 - Margaret Martineau: 'at Neath comes the end of the beauties. A thick smoke closed the scene and we drew in copper at every breath.'

1850 - Ellen and Emily Hall: 'Drove to the Valley of Neath, much choked at times, with the terrible copper smoke – Up to this little town the valley is all more or less injured by the effluvia from the works – but after passing that, the green trees look fresh and healthy. … Before the whole country side was blasted and destroyed by this abominable copper smoke the situation of Neath Abbey ruins must have been most lovely.'

1861 - Samuel Carter Hall: 'Neath is now a town of smoke through which its rare and valuable antiquaries are all too often but barely seen.'

Everyone knew the problem but how to deal with it was another matter. A prize fund was established in Swansea in 1821 'for obviating the inconvenience arising from the smoke produced by smelting copper.' A number of ideas were put forward but none were deemed worthy of an award.

In 1832 at the instigation of Dr (later Sir) Charles Hastings, physician at Worcester Infirmary, meetings were held in different towns and cities of the United Kingdom each year to discuss the national problem of smoke pollution and to endeavour to come up with a solution. In Swansea the works were 'zoned' on the edge of the town so that the smoke was carried by prevailing winds over wasteland to the east; but in Neath the smoke from the copper works was carried by the same winds towards Neath town.

From Llanelli to Neath there were so many copper works that the area became known as ‘Copperopolis’. South Wales was reckoned to account for up to 90% of the United Kingdom’s copper production and 50% of the global supply.

Stac-y-Foel was built above Cwmavon in the 1830s, the intention being to keep the smoke away from the town. The structure, 1200 feet above sea-level, had the desired effect but although the smoke dispersed, the dust settled on more distant parts, including the Vale of Neath as far away as Rheola. 'It settled upon and destroyed the grass for twenty miles around, while the sulphur and arsenic in the fumes affected the hoofs of the cattle, causing gangrene.' Nash Edwards Vaughan of Rheola did try to whip up support to take on the copper companies and called a meeting of landowners at the Castle Hotel on 27th May 1860, but only ten or twelve (the press were not admitted) attended, led by Howel Gwynn, J. Bruce Pryce and J. T. Llewellyn. A committee was formed and subscriptions taken but nothing more is heard and the lack of support must have been disappointing.

Stac-y-Foel was built above Cwmavon in the 1830s, the intention being to keep the smoke away from the town. The structure, 1200 feet above sea-level, had the desired effect but although the smoke dispersed, the dust settled on more distant parts, including the Vale of Neath as far away as Rheola. 'It settled upon and destroyed the grass for twenty miles around, while the sulphur and arsenic in the fumes affected the hoofs of the cattle, causing gangrene.' Nash Edwards Vaughan of Rheola did try to whip up support to take on the copper companies and called a meeting of landowners at the Castle Hotel on 27th May 1860, but only ten or twelve (the press were not admitted) attended, led by Howel Gwynn, J. Bruce Pryce and J. T. Llewellyn. A committee was formed and subscriptions taken but nothing more is heard and the lack of support must have been disappointing.

The Towns Improvement Clauses Act of 1847 (section 108) tried to address the issue. It stated that any furnace constructed after the passing of the Act should be constructed so as to consume the smoke arising. All well and good, but in Swansea the council were more concerned with such action placing them at an economic disadvantage with their competitors. When a motion was put to them to enact section 108 it was almost unanimously rejected 'and the copper smelters may make as much smoke as they please without molestation.'

Coppermasters argued that the smoke was beneficial. In a Report to the Board of Health in 1854, Dr Thomas Williams of Swansea said that the presence of copper smoke was in fact extremely beneficial since its antiseptic properties acted as a protective cordon to keep disease at bay. As it contained sulphur and arsenic there were probably not many who agreed with him!

Dr Williams added that 'there were about 300 furnace chimneys near Swansea and the region was practically denuded of vegetation as a direct result of the action of sulphurous copper smoke which, in fifteen decades of smelting operations, had transformed the smiling valley into a barren desert. Drifting before the wind, the lurid vapours darkened the air, concealed the sun and stifled the breather. The fumes emanating from the stacks of the furnaces, consisting of the combined products resulting from roasting the copper ore and the combustion of coal, had helped to pollute the soil and render it sterile. With the exception of wild chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla) not a tree, shrub or blade of grass could be seen anywhere in the locality.'

Getty Images - public domain

The problem in Neath seems to have disappeared by 1870 as newspaper complaints trickled out. Perhaps this was due partly to copper works moving further down the valley to the Red Jacket area although the Crown Copper Works at Neath Abbey continued until 1881. The move, however, merely shifted the problem elsewhere.

In 1853 a Birmingham land agent named Dougdale Houghton bought the leases of two farms Coedyrallt Uchaf and Coedyrallt Isaf. His family had business interests in Briton Ferry, Tonmawr and Cadoxton from the early years of the century but this was one venture that did not bear fruit. Ten years after his purchase he took Arthur Bankhart, proprietor of the Red Jacket Copper works, to the Glamorgan Assize where he claimed over £8,000 in damages. His claim was listed for the three years 1857-1859 and showed claims for loss of sheep, horses, cattle, rabbits (there was a warren on the land and because the animals were affected by the poisoned ground they could not be sold), barley, oats, wheat, hay, clover, turnips, grass etc..., etc… It was claimed that the nearby copperworks had, when it opened, adopted methods to deal with the smoke (originally it was a spelter works), but these methods had more recently been abandoned and the smoke 'impregnated the land and air; the air breathed by the plaintiff’s cattle were thereby injured and by eating the grass.… died.' Houghton was believed by the reporter to have been offered £1,700 compensation before the three-day trial but refused. The jury eventually awarded a paltry £150 damages but did state that the copper works was a nuisance and that it was not in a convenient place. Houghton had previously been awarded damages of £450 in a similar case for the years 1855-6.

Elsewhere the effects continued unabated and did not end until the mid-1890s when competition from abroad meant local production was not profitable.

According to the World Health Organisation, today over four million people suffer premature deaths each year due to air pollution – only the pollutants have changed.

SOURCES

The Environmental Impact of Industrialisation in South Wales in the Nineteenth Century: Copper Smoke and the Llanelli Copper Company - Edmund Newell and Simon Watts (1996)

The South Wales Copper Smoke Dispute 1833-1895 - Roland Rees (Welsh History Review 1980)

Evading constraints? 200 years of uncontrolled pollution by the Swansea copper industry - Malcolm Bailey [Open University dissertation] (2019)

Copper Industry - Clive Trott (Neath & District - A Symposium 1974)

Various newspapers